Although at first glance, Izmir isn’t as beautiful as Istanbul, visitors there will discover a fascinating food culture – which include a seriously addictive treat.

By Ronit Vered

Haaretz Contributor

Pomegranate and citrus trees grow in the cortejos (courtyard houses) of the old Jewish Quarter of Izmir, a city of some 4.25 million people on Turkey’s Aegean coast, formerly known as Smyrna. “Trees like this, whose fruit are part of Jewish religious ritual, are always an indication of a Jewish presence,” says Nüket Franco, a local culinary tour guide. In centuries past, Sephardi Jews sat in the shade of the pomegranate, lemon and citron trees here, having found refuge in the Ottoman Empire after being expelled from Spain and Portugal. At present, refugees and labor migrants from African countries and from Syria sit in the shade of those same trees.

Beginning in the 15th century, the Ottoman sultans granted haven to Jewish refugees when other kingdoms expelled or shut their gates to them. Even 600 years later, few countries, the Jewish state among them, allow the persecuted and the downtrodden to build a new life within their territory. For many of the latter-day refugees, Izmir is a way station to an unknown future. Most of them dream of obtaining legal visas to Canada or Europe; in the weeks ahead, some of them will probably try to make the perilous sea crossing to Europe illegally. (There are stores here selling used, pathetic-looking life jackets.)

The courtyard houses were built by Jews who fled the Inquisition according to the designs and lifestyle they had been familiar with in the Iberian Peninsula: a shared, inner courtyard – spacious and hidden from the street, with running water and washing and cooking facilities – surrounded on all sides by two-story residences for poor families, without washrooms and kitchens.

“The Jews were ordered to leave their property behind in Spain,” Franco explains, “and many of the Jews who settled in Izmir were destitute at first. The courtyard houses were meant for people who couldn’t afford to buy a home of their own, and the fact that they lived together created solidarity and a sense of shared destiny.”

In recent years, some of these historic courtyard houses, as well as other buildings in the Juderia (Jewish Quarter) that were abandoned by their residents in the first half of the 20th century, have been turned into hostels and cheap hotels. Refugees from African countries and Syria live in them, exactly as the Jews did in their day. They sleep in as families in single rooms with balconies overlooking the courtyards, where they spend most of their waking hours, cooking, washing and doing laundry. The rent they pay is 20 Turkish lira a day ($2.85) – yet even that sum is too much for many of the newcomers.

Trauma and loss

We continue in the direction of one of Izmir’s lovely old tea houses in order to try the local çay (“tea,” in Turkish), a strong, black brew, in the shade of fig trees. In the early 20th century, proprietors of tea and coffee shops kept personal porcelain cups in glass cabinets for their regular clients. These days everyone uses standard glasses, but the cabinets – still containing dazzling collections of porcelain tea sets – still adorn the walls. Wooden chests hold packs of cards and boxes of Rummikub (a game that combines elements of rummy and mahjong), very popular among residents here.

Even in the broiling heat of August, a breeze from the bay reaches almost every corner of this hilly city. But it was also a pleasant wind that intensified the catastrophe one terrible day in mid-September 1922, during the Greco-Turkish War, when huge swathes of the city began to be consumed by flames that were only extinguished after nine days.

Credit: Ronit Vered

Franco: “Because of the wind, the fire spread quickly. The ancient Muslim Quarter suffered less because of where it was located, but the other quarters, where Armenians, Greeks and Jews lived, were almost completely burned to the ground, and many of the residents fled. The Greek Christians were expelled as part of a population exchange between Greece and Turkey in 1923.”

The trauma and loss endured by communities that resided in Izmir for hundreds of years, and the eventual disappearance of many aspects of cultural-historical heritage, continue to resonate in Izmir to this day.

Franco, who comes from a Sephardi family whose roots are in Malaga, was born in Istanbul and only moved to Izmir in 1980, after she got married.

“Today I can no longer imagine life in Istanbul,” she says, with a smile. “Izmir is smaller, and if you live in the center you can get everywhere on foot. There’s a feeling of freedom here that you don’t find in other places. It’s still considered one of the most secular and most liberal cities in Turkey, even though in the past few decades large waves of immigration from southern and eastern Turkey have begun to change the composition of the population and also its political leanings. With the political shifts we are also getting many intellectuals and creative people, who are leaving Istanbul.”

In 2010, Franco and five other local women wrote and edited a cookbook of nearly 100 traditional recipes from Izmir’s Sephardi community. What began as a modest pamphlet in Turkish morphed in 2012 into an English-language book, “Izmir Sephardic Cuisine.”

“I come from a very secular family,” she explains, “but I was a volunteer in the League, a Jewish cultural center. We looked for creative ways to document and preserve the Jewish heritage and identity for the young generation. Many of the recipes in the book – which we collected from mothers, mothers-in-law, aunts and neighbors – are hardly ever used today. In some cases, because they are complicated and demand skills that have been lost; in others, because they do not fit in with current conceptions of nutrition.”

In the past two years, Franco has been guiding tours of Izmir through the worldwide Culinary Backstreets project (on which more below). Her fascinating six-hour tour focuses – like the tours the firm offers in other cities – on restaurants that feature home-style cooking, and on street-food stalls, small-scale food manufacturers and other hidden sites that are not easily accessible to tourists.

Izmir, at first glance, is not as beautiful as Istanbul. Many of the buildings in one of the world’s oldest and most fascinating cities were destroyed in wars that raged in the 20th century, and were hastily replaced – in a pattern familiar from Eastern Europe after World War II – with bland and dreary modern structures. The archaeological treasures of this city, an important port in the classical age, are displayed in an archaic style in museums empty of visitors that the authorities seem to lack any interest in (perhaps because the most intriguing exhibits attest to a past that is not consistent with the contemporary political narrative). But echoes of Izmir’s diverse cosmopolitan past, and of the life that existed here when it constituted an important commercial junction between East and West, can easily be gleaned from the culinary standpoint and the riveting food culture here.

Credit: Dan Perez

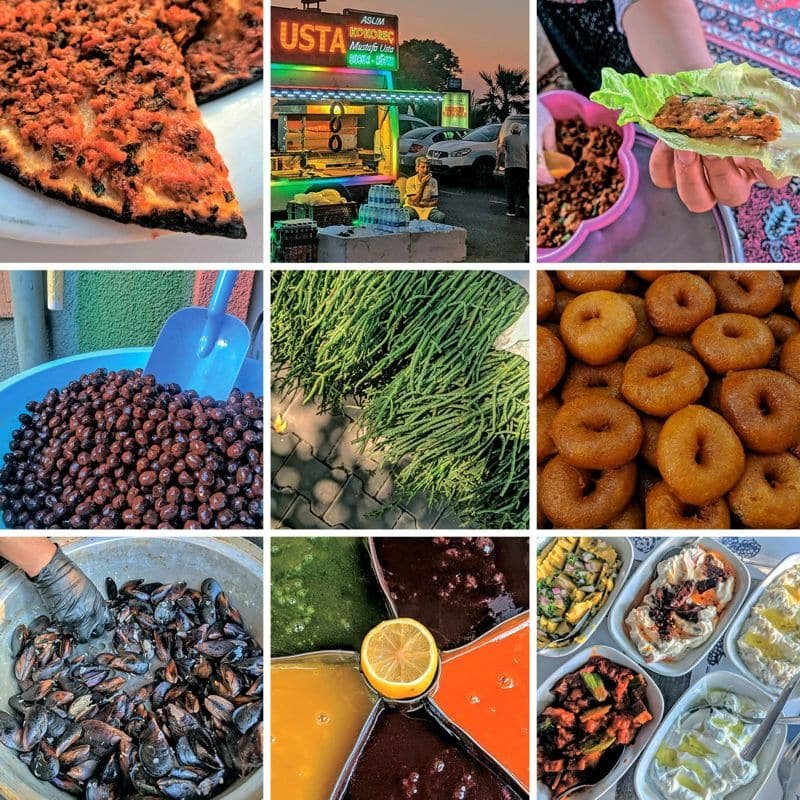

One of the city’s most interesting sites is the famous Kemeralti Market. This stunning Ottoman-era bazaar, which dates from Izmir’s golden age in the 17th century, sprawls across several square kilometers, from the ancient agora to the seaside wharf. It’s divided into sub-markets according to specialties: clothing, jewelry, kitchen utensils and knives, food, coffee and tea shops, and so on.

Nestled amid the tangle of alleys and khans are alluring culinary establishments: shops where elderly vendors still prepare cool, homemade sherbet; stalls selling semolina cookies, kaymak (a clotted-cream delicacy) and macun, a soft fruit toffee seasoned with honey and spices, whose origins are intertwined with the preparation of medications in antiquity; fresh fruit and vegetables of rare local varieties; restaurants featuring grilled foods (there are 291 types of dumplings in the Ottoman gastronomic universe, and in Izmir’s market I’m pretty sure I sampled the best of them); fish and shellfish restaurants; and eateries featuring homemade dishes that evoke the various minority communities that were an integral part of the city’s history.

Although Izmir lies on the shores of the Aegean and has a charming bay-side boardwalk, it has no sandy beaches. To bathe in the sea, locals and tourists travel to Çesme and other coastal towns, situated about half an hour’s drive away. The absence of beaches, together with the destruction wrought to the streets and buildings during the Greco-Turkish War a century ago, are among the reasons that Izmir has yet to become a major tourist destination. This is reflected not only in the neglected museums, but also in the fact that I was unable to find even one store selling English-language tourist guides or books about the city, past or present. The upside of all that is the low rates at hotels, even those on the water, and of course at the restaurants and food stalls.

Why Izmir?

One of the foods most associated with Izmir is boyoz, a round pastry of thin, oiled layers of flaky dough – a delightful delicacy that’s hard to find elsewhere. Sold at local bakeries and from peddlers’ carts, it’s eaten as is, without a filling, accompanied by tea and a hardboiled egg; alternatively, the pastry can be split open and eaten, sandwich-like, with cheese, tomato, spicy green peppers and olives. There’s no one who was born or lives in Izmir who isn’t familiar with the popular treat – but not everyone knows that its name comes from Ladino, the language of the Sephardi community that sought refuge in Ottoman lands after the expulsion from Spain.

Legend has it that the Jews of Izmir brought the pastry and the technique for preparing it from the Iberian Peninsula, and shared it with the Muslims and Christians of the Ottoman city. But the current version of boyoz sold in Izmir typically has no filling (the Jewish version includes a filling of cheese, spinach or eggplant, and is similar to what in Israel is called a “Turkish burekas”). The technique of flattening dough to a thin layer and creating layered pastries is associated more with the Turkish peoples of Central Asia. And if the original recipe was imported from Spain, we wonder, why is Izmiri boyoz different from pastries with the same name that are so popular among Sephardi Jewish communities elsewhere? And why did boyoz become a popular pastry that exceeded the boundaries of the Jewish community precisely in Izmir and not, say, in Istanbul?

Credit: Ronit Vered

Credit: Ronit Vered

The answers to these questions, as with other dishes that have a long and rich history, are both simple and complex. Foods change with time, though often they continue to bear the same name. Attempts to discover when the changes occurred or who is responsible for them, are generally doomed to failure. Local delicacies with ancient histories typically reflect the fraught transformations that have taken place in the lives of the people and the communities that prepare and consume them.

Fuente: haaretz.com

eSefarad Noticias del Mundo Sefaradi

eSefarad Noticias del Mundo Sefaradi