As mentioned in the previous post, a proposed new law would provide a fast track for Sephardic Jews to obtain Spanish citizenship. What remains murky, however, is who exactly would be counted under that law as a “Sephardic Jew”. Leaving aside the descendants of “conversos”, that is Jews who converted to Christianity under duress during the Spanish Inquisition and are thus no longer Jewish (discussed in the previous post), even for bona fide Jews it would not be easy to prove ties to Spain’s pre-expulsion Jewish community. Malcolm Hoenlein, the executive vice chairman of the Conference of Presidents of Major American Jewish Organizations, called the definitional issues “a bureaucratic nightmare” during his recent visit with Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy and King Juan Carlos.

One problem has to do with the term “Sephardic” itself. In Hebrew, the term originally meant ‘pertaining to Spain’, or Sepharad. But over time, the label has come to apply to one of the two main variants of Jewish religious practice, the other one being the “Ashkenazic” rite. The Sephardic liturgy is somewhat different from the Ashkenazic one, and Sephardim use different melodies in their services. Sephardic Jews also have different holiday customs and different traditional foods: Ashkenazic Jews eat latkes (potato pancakes) to celebrate Chanukkah, while Sephardic Jews eat sufganiot (jelly doughnuts)—though many Jews today eat both. The best-known difference in religious practices relates to the holiday of Pesach (Passover): Sephardic Jews may eat rice, corn, peanuts, and beans during this holiday, while Ashkenazic Jews avoid such foods, alongside wheat, rye, and other traditional grains. Culturally, Sephardic Jews have generally been more integrated into the local non-Jewish milieu than Ashkenazic Jews. The latter lived mostly in Christian lands, where the tensions between Jews and Christians ran high, so the Jews tended to be isolated from their non-Jewish neighbors, either voluntarily or involuntarily. Sephardic Jews more often than not found themselves in Islamic lands, where historically there was less segregation and oppression. Sephardic Jewish thought and culture was strongly influenced by Arabic and Greek philosophy and science. Even the pronunciation of Hebrew differs for Sephardic and Ashkenazic Jews.

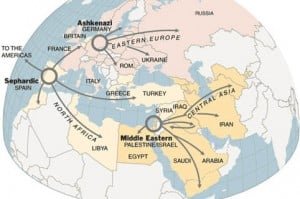

Most Jews who follow the Sephardic custom hail from northern Africa and southern Europe, where they settled upon expulsion from Spain. But other communities, from places like Iraq, Iran, Yemen, and Syria, are considered Sephardic by religious practice yet may not fall under the new Spanish law if the definition is narrowed to people with historical links to Spain. The Yemenite and Iranian Jewish communities do not descend from Iberian exiles, and the Syrian and Iraqi Jewish communities descend only in part from Iberian refugees. Yet “all but the Yemenites adhere to Sephardic customs, and even the Yemenites follow some Sephardic sages”, according to an article in Haaretz. As a result, Jewish communities from Egypt, Iraq, Iran, Yemen, and Syria are sometimes placed in third category as “Middle Eastern” or “Oriental” Jews (see map).

Most Jews who follow the Sephardic custom hail from northern Africa and southern Europe, where they settled upon expulsion from Spain. But other communities, from places like Iraq, Iran, Yemen, and Syria, are considered Sephardic by religious practice yet may not fall under the new Spanish law if the definition is narrowed to people with historical links to Spain. The Yemenite and Iranian Jewish communities do not descend from Iberian exiles, and the Syrian and Iraqi Jewish communities descend only in part from Iberian refugees. Yet “all but the Yemenites adhere to Sephardic customs, and even the Yemenites follow some Sephardic sages”, according to an article in Haaretz. As a result, Jewish communities from Egypt, Iraq, Iran, Yemen, and Syria are sometimes placed in third category as “Middle Eastern” or “Oriental” Jews (see map).

Whether the religious or historical definition of “Sephardic” is used in the law, the Spanish legislation proposes an operational definition that is dependent on accreditation by Jewish authorities: one is a Sephardic Jew if some Jewish authority says so. One possible way to prove that one is a Sephardic Jew would be to receive a certificate from the Federation of Jewish Communities in Spain, even though the law does not specify how the federation can make that determination. Potential applicants may also present documentation from local rabbinical authorities in their countries of origin, but there is a snag with this option too: as reported in the articlein Forward Thinking, the law states that “those rabbis should be ‘legally recognized’ — a category that doesn’t exist in the United States, where there are no state-recognized religious authorities”.

Beside the religious rite, which is used also by Jews with no historical ties to Spain, Sephardic customs include culinary sensibilities (as mentioned above) and an extensive oral narrative tradition. But such cultural attributes are difficult to write into law. Therefore, potential applicants may be able to prove their ancestry by having a surname of Spanish origin or providing evidence that their family speaks Ladino (also known as Judeo-Spanish, Dzhudezmo, Judezmo, and in Morocco as Hakitía). But only a small proportion of the world’s Sephardic Jews would qualify according to either of those two tests. Ladino, a Jewish language based on 15th-century Castillian Spanish with elements of Hebrew and other Jewish languages, was once spoken by Sephardic Jews everywhere. However, the rise of nationalism in the Balkans, North Africa and the Middle East, the assimilatory tendencies in the Americas, the persecution of Jews during World War II, and the earlier Israeli policies of promoting Hebrew at the expense of other Jewish languages led to the endangerment of Ladino worldwide. According to Shmuel Refael of Bar Ilan University, only about 250,000-300,000 people in Israel have “some potential knowledge of Ladino”. The Ethnologue cites an even smaller figure of 100,000 speakers in Israel in 1985 and a total of 112,130 in all countries.

The surname test is problematic as well. Since no official list of such surnames came from the Spanish authorities, the popular Israeli newspaper Yediot Aharonot published an inventory of more than 50 traditional Sephardic surnames, including Abutbul, Medina, and Zuaretz. Surnames, however, only track paternal ancestry. This brings up the complicated issue of bloodline: how many Sephardic grandparents does one have to have in order to qualify and does it matter if they are from the paternal or maternal side? The current draft of the Spanish legislation does not wade into those murky waters and makes no mention of genetic testing either. This appears to be a sensible decision, as there are no clear “Sephardic” genetic markers. In terms of Y-DNA, Sephardic Jews have a higher proportion of haplogroups R1b (29.5%, compared to 11.4% among the Ashkenazic Jews) and I (11.5%, compared to 4% among the Ashkenazic Jews). This is unsurprising as these two haplogroups are found in the highest frequency in Atlantic Europe and the Balkans, respectively, two areas where Sephardic but not Ashkenazic Jews settled in large numbers. Ashkenazic Jews, in contrast, have a higher frequency of haplogroups J (43% compared to 28.2% among Sephardic Jews) and E1b1b (22.8% compared to 19.2% among Sephardic Jews), which have been carried on since pre-Diaspora times (Haplogroup J is most common in the Middle East and haplogroup E1b1b is widespread in the Horn of Africa.) Such patterns further support the abovementioned generalization that Ashkenazic Jews remained more isolated from their host populations than Sephardic Jews. (These data are from Nebel, Filon, Brinkmann, Majumder, Faerman, and Oppenheim, “The Y Chromosome Pool of Jews as Part of the Genetic Landscape of the Middle East”, American Journal of Human Genetics 2001, 69(5): 1095-1112.) The upshot of this discussion is that there is no haplogroup or mutation that unambiguously identifies Sephardic Jews.

The surname test is problematic as well. Since no official list of such surnames came from the Spanish authorities, the popular Israeli newspaper Yediot Aharonot published an inventory of more than 50 traditional Sephardic surnames, including Abutbul, Medina, and Zuaretz. Surnames, however, only track paternal ancestry. This brings up the complicated issue of bloodline: how many Sephardic grandparents does one have to have in order to qualify and does it matter if they are from the paternal or maternal side? The current draft of the Spanish legislation does not wade into those murky waters and makes no mention of genetic testing either. This appears to be a sensible decision, as there are no clear “Sephardic” genetic markers. In terms of Y-DNA, Sephardic Jews have a higher proportion of haplogroups R1b (29.5%, compared to 11.4% among the Ashkenazic Jews) and I (11.5%, compared to 4% among the Ashkenazic Jews). This is unsurprising as these two haplogroups are found in the highest frequency in Atlantic Europe and the Balkans, respectively, two areas where Sephardic but not Ashkenazic Jews settled in large numbers. Ashkenazic Jews, in contrast, have a higher frequency of haplogroups J (43% compared to 28.2% among Sephardic Jews) and E1b1b (22.8% compared to 19.2% among Sephardic Jews), which have been carried on since pre-Diaspora times (Haplogroup J is most common in the Middle East and haplogroup E1b1b is widespread in the Horn of Africa.) Such patterns further support the abovementioned generalization that Ashkenazic Jews remained more isolated from their host populations than Sephardic Jews. (These data are from Nebel, Filon, Brinkmann, Majumder, Faerman, and Oppenheim, “The Y Chromosome Pool of Jews as Part of the Genetic Landscape of the Middle East”, American Journal of Human Genetics 2001, 69(5): 1095-1112.) The upshot of this discussion is that there is no haplogroup or mutation that unambiguously identifies Sephardic Jews.

Moreover, virtually all Jews today have some Sephardic forebears, if Joshua S. Weitz, a professor at the Georgia Institute of Technology is to be believed. A director of a quantitative biosciences group at Georgia Tech, Weitz built a genealogical model of Jewish ancestry; in a draft paper based on this model and published on the academic website arXiv.org in October 2013 he summarizes his findings as follows: “nearly all present-day Jews are likely to have at least one (if not many more) ancestors expelled from Spain in 1492”.

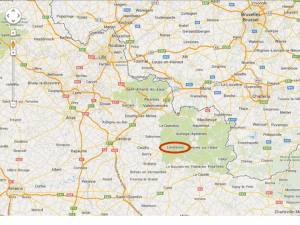

The intertwining of distinct Jewish lineages—Sephardic, Ashkenazic, and others—into a complex tapestry of today’s Jewish genealogy also points to another problem with the surname test: family names can be, and often have been, changed or adopted. A case in point: a Jewish family evicted from Spain settles in northern France, and one of their descendants joins the army of Napoleon Bonaparte, crosses Europe, and is wounded in Russia’s Pale of Settlement (today Belarus), where a local Jewish woman (almost certainly of Ashkenazic descent) nurses him back to health, they fall in love—and the rest is history. My family’s history. In my youth, I did not give much credence to this family legend, as it seemed a little too far-fetched. But with the advent of Google Maps and Wikipedia, I have been able to ascertain some of the legend’s details that made the story sound plausible. According to the legend, my paternal grandmother’s maiden surname, Lyandres, came from the name of the home town of this unfortunate soldier: when he was asked what his surname was, he would merely repeat the name of the town he wanted to be sent back to (I am guessing this was before the falling-in-love part!). The town was supposed to be near the Belgian border (or, according to an alternative version, in Belgium now, but part of France in 1812). The maps of France available in the Soviet Union in my childhood showed no such toponym, and French spelling possibilities were seemingly endless, so I abandoned the search. I returned to the project more recently, however, deciding to use Google Maps to search again. I zoomed into various areas of northern and northeastern France—and lo and behold, there it was, about 20 miles east of Cambrai and 15 miles south of the Belgian border (see map on the left). A Wikipedia search revealed Landrecies to be a small commune, population 3,858, in the Nord department of the Nord-Pas-de-Calais region in northern France. Beside my esteemed ancestor, Landrecies was also the hometown of Joseph Francois Dupleix, governor of French India under King Louis XIV, and more recently of former Tour de France director Jean-Marie Leblanc. There is even another Napoleonic-era connection: Henri Jacques Guillaume Clarke, Napoléon’s Minister of War and later a marechal, was born in Landrecies in 1765.

The intertwining of distinct Jewish lineages—Sephardic, Ashkenazic, and others—into a complex tapestry of today’s Jewish genealogy also points to another problem with the surname test: family names can be, and often have been, changed or adopted. A case in point: a Jewish family evicted from Spain settles in northern France, and one of their descendants joins the army of Napoleon Bonaparte, crosses Europe, and is wounded in Russia’s Pale of Settlement (today Belarus), where a local Jewish woman (almost certainly of Ashkenazic descent) nurses him back to health, they fall in love—and the rest is history. My family’s history. In my youth, I did not give much credence to this family legend, as it seemed a little too far-fetched. But with the advent of Google Maps and Wikipedia, I have been able to ascertain some of the legend’s details that made the story sound plausible. According to the legend, my paternal grandmother’s maiden surname, Lyandres, came from the name of the home town of this unfortunate soldier: when he was asked what his surname was, he would merely repeat the name of the town he wanted to be sent back to (I am guessing this was before the falling-in-love part!). The town was supposed to be near the Belgian border (or, according to an alternative version, in Belgium now, but part of France in 1812). The maps of France available in the Soviet Union in my childhood showed no such toponym, and French spelling possibilities were seemingly endless, so I abandoned the search. I returned to the project more recently, however, deciding to use Google Maps to search again. I zoomed into various areas of northern and northeastern France—and lo and behold, there it was, about 20 miles east of Cambrai and 15 miles south of the Belgian border (see map on the left). A Wikipedia search revealed Landrecies to be a small commune, population 3,858, in the Nord department of the Nord-Pas-de-Calais region in northern France. Beside my esteemed ancestor, Landrecies was also the hometown of Joseph Francois Dupleix, governor of French India under King Louis XIV, and more recently of former Tour de France director Jean-Marie Leblanc. There is even another Napoleonic-era connection: Henri Jacques Guillaume Clarke, Napoléon’s Minister of War and later a marechal, was born in Landrecies in 1765.

The upshot of this story is that it is quite possible—though not yet conclusively proven—that at least one branch of my family tree contains Sephardic forbearers. Yet their surname was most definitely changed, and this being a maternal line on my father’s side, the original surname would not have been passed down to me (or to my father). Once our “French ancestor” settled in an Eastern European shtetl, he assumed the Ashkenazic customs of his adoptive community and probably spoke Yiddish as well; his descendants most certainly did. All in all, even if he was of Sephardic descent, there is hardly enough evidence to prove my “Sephardic ancestry”, I suspect—and still, I sometimes make traditional Sephardic dishes on Passover to honor his memory.

May 19, 2014 by Asya Pereltsvaig

Source: Languajes of the world

eSefarad Noticias del Mundo Sefaradi

eSefarad Noticias del Mundo Sefaradi

Buen Estudio. Interesante

The last name test can. E useful however, if you’re a descendant of anousim, Mexico especially, families tended to marry within their Jewish community. So you will see sometimes 4 and 5 surnames repeated over and over. If they all happen to be sephardic in origin there’s a good chance you’re descended from sephardic Jews. The Catholic Church has records of names they identified as being Sephardic Jewish in origin. If you find several of your family’s surnames on the list there’s a good chance your family were cryptojews or conversos.

yes my mother’s mother born in Sonora Mexico her line goes back from Spain devote catholic line how do I find out about history of m sepahrdic line> names are navarrete, angulo campillo montano martinez forte landavazo so forth carrillo