Anyada Buena, Dulse i Alegre!

The Jewish people celebrate Rosh Hashana (pronounced Rosh Ashana among Sepharadim) every year starting the evening of the first day of the Hebrew month of Tishri. The Jewish New Year is celebrated in synagogues by hearing the shofar (ram’s horn) blasts and at home with a festive meal with symbolic foods, like apples dipped in honey for a sweet new year.

At the beginning of the festive dinner, Sephardic Jews from the lands of the former Ottoman Empire have a special custom called the yehi ratzones, a series of symbolic appetizers including not only apples, but also dates, leeks, spinach, squash, black-eyed peas, and cheek meat of a cow or a fish head (the foods may differ between communities and be prepared in any number of ways). The symbolic foods represent, based on word play with Aramaic or Hebrew, a hope for the coming year, yehi ratzon meaning “may it be [God’s] will.” For instance, dates symbolize the hope for the end of enmity against the Jews, as the Aramaic word for “date” is similar to a Hebrew word for “end.” The fish head or cheek meat symbolizes our hope that we may be the head, and not the tail. (See the order of the yehi ratzones in English, Hebrew and Ladino [in Latin script] according to the Sephardic customs as practiced in Seattle in Isaac Azose’s Mahzor Tefilah Le-David Le-Rosh Ashana.)

It is not entirely clear where the custom of the yehi ratzones originates, but food symbolism dates back to Talmudic times. In addition to the yehi ratzones, instead of dipping their bread in salt as is customary throughout the year, Jews dip their bread in honey or sugar on Rosh Ashana. In Rhodes, that sugar was kept throughout the year for various folk remedies. In her memoir I Remember Rhodes, Rebecca Amato Levy relates another interesting custom followed by this community in which they avoided wearing anything new on their feet including shoes, stockings, and slippers on Rosh Ashana.

Sepharadim greet each other with the Ladino expression Anyada Buena, Dulse i Alegre (“May you have a good, sweet and happy New Year”) or a Hebrew greeting, Tizku leshanim rabot (“May you merit many years”), to which one answers, Tizkeh vetihyeh ve-ta’arich yamim (“May you merit and live and increase your days”).

As part of our Sephardic Studies Digital Library and Museum at the University of Washington, we have several sources that offer us insight into the Jewish New Year as conceptualized by Sephardic Jews in the previous century.

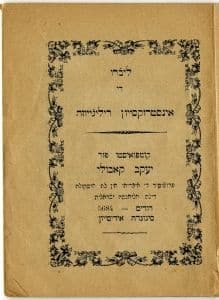

One of the most intriguing of these texts comes from 1923/1924 on the island of Rhodes, then part of Italy. Ya’kov Kabuli, a teacher of Hebrew at one of the schools of the Alliance Israélite Universelle on Rhodes, published the second edition of his Livro de Instruksion Relidjioza. As implied by the title of the booklet, “Book of Religious Instruction,” it was intended for children in the Jewish schools in the “Orient” (meaning primarily the Eastern Mediterranean). Given the geographic proximity of Rhodes to mainland Turkey, the last page of the book indicates that it was also available for sale in the port city of Izmir, home to a much larger Sephardic Jewish community also part of the “Orient.”

______________________________________________________

Ty Alhadeff is the Sephardic Studies Program Coordinator of the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies at the UW. Ty is a graduate of the University of Washington and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel.

______________________________________________________

This article originally appeared on jewishstudies.washington.edu, the website of the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies at the University of Washington. Reprinted here with permission.

______________________________________________________

Source: Stroum Center for Jewish Studies

eSefarad Noticias del Mundo Sefaradi

eSefarad Noticias del Mundo Sefaradi