Michal Held

The Center for Study of Jewish Languages and Literatures, The Hebrew University, Jerusalem

Introduction

From the start of the twentieth century, the status of JudeoSpanish [1] has seriously deteriorated because of various social developments, chief among these being the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, the Nazi extermination of the JS speaking Jews of the Balkans, the rise of Zionism and the revival of Hebrew.

From the start of the twentieth century, the status of JudeoSpanish [1] has seriously deteriorated because of various social developments, chief among these being the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, the Nazi extermination of the JS speaking Jews of the Balkans, the rise of Zionism and the revival of Hebrew.

Having lost its function as a vital a tool of communication, contemporary JS used online may be regarded as a metaphoric place, in which an identity is constructed in the absence on a offline Sephardi community. The new Sephardi courtyard forming on the Internet is based primarily upon the ethnic language: the vehicle for the recreation of a fragmented offline personal and collective Sepahrdi identity. Thus, a replacement for the Sephardi homeland (or rather the system of homelands that Sephardi Jews yearn back to, such as Eretz Israel and Jerusalem, Spain, the Ottoman Empire, the State of Israel–to name just a few) is being constructed.

One way of deciphering the online Sephardi activity is in the light of Benedict Andreson’s definition of the Imagined Community, [2] as the reconstruction of an imagined Sephardi identity based upon a culture that has none or very little function in today’s offline world. The following paper shall offer such an analysis of it while demonstrating the move from concrete to virtual Sephardi life, focusing on the Internet as a territory where a culture may be revitalized after having faced a state of severe decline. The key concept deriving from the discussion is a proposed new phase in ethnic and folkloristic thought: The Digital HomeLand, a concept that illuminates not only the contemporary Sephardi situation, but also general aspects of human culture that is situated at a turning point in the technological age.

JudeoSpanish Online Communities: The Current Situation

My interest in the phenomenon of online communities in general, [3] and in its Sephardi version in particular, started in the year 2000, when I visited South Africa during the Jewish High Holidays. My local friends did their best to make my stay a pleasant one. One thing, however, they hadno idea how to help me find -and that was a Sephardi synagogue. A solution came from Ladinokomunita: a JS online community that was taking its firs steps on the Internet at the time. A member of this circle directed me to the Sephardi synagogue in Cape Town, where I ended up celebrating Rosh Hashana with the community of the descendants of the JS speaking Jews whose parents and grandparents had emigrated from the Greek Island of Rhodes to Africa in the 1930s.

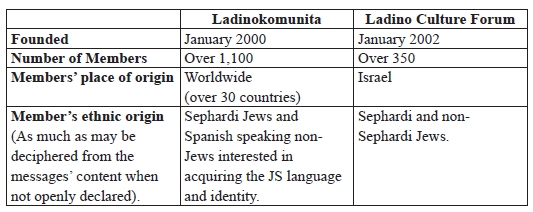

This anecdote emphasizes the role that the Internet plays in contemporary Sephardi life. Towards the dawn of the twenty-first century when JS almost ceased to exist as a spoken language, the Sephardi phoenix surprisingly arose from its ashes in the terra incognita of the World Wide Web. The new process may be demonstrated by an analysis of two active JS online communities: The Ladinokomunita Mailing List, hosted by Yahoo groups [4] and The Ladino Culture Forun, hosted by the Israeli web portal Tapuz. [5] Interestingly enough, the difference between the titles represents two levels of virtual reconstruction of Sephardi life: community and culture. [6] Methodologically, I investigated the JS online communities with the tools used in folcloristic fieldwork and those relevant to a muldisciplinary approach to JS studies. The developing research method called cyberethnography (“an internet technologically mediated and enabled hypertextual/intertextual performance”) [7] was also employed in my digital fieldbook, in wich it enphatized crucial dilemas such as the need to redifferentiate between the private and the public sphere, and between the written and the multimediapresented material.

The following table represents the activity in the JS online communities in December 2009:

The central topics of both circles are the following:

- JS language, including attempts to decipher meanings and origins of words and personal and family names and to acquire, or reacquire,the language Sephardi culture: music, literature, folk songs, proverbs, material culture Sephardi cuisine, and in particular the attempts to reproduce lost linguistic and practical dimensions of it

- History and genealogy of the Sephardi communities in Israel and around the world

- Past experiences related to Sephardi tradition and communities

- Jewish holidays in the Sephardi tradition

- Contemporary literary creation in JS

- Sephardi events and publications

- Biblical commentary

- Personal affairs (birthdays, weddings, condolences)

An online JS dictionary is being compiled in both circles, and in Tapuz a collection of articles devoted to JS language and culture is also available.

As the listo of topics, the JS online communities concentrate manily on specific Sephardi issues. The particpants rarely present general affairs (political, economical, cultural, etc.). By limiting the subject matter of their interactions to their ethnic concerns, they create a Sephardi enclosure that can exist more easily in the virtual realm than in the concrete world in our times.

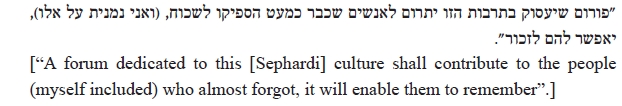

Conceptual Framework The JS online communities’ founders and moderators emphasize that a central aspect of the raison d’être of the activity that they started online in JS is to preserve and revive Sephardi memory. “Vamos a korrespondermos en muestra kerida lingua para ke no mos ulvidemos de eya” (we are going to correspond in our dear language so that we do not forget her), says Rachel Bortnik of Ladinokomunita. Ruti B. of the Tapuz forum claims that:

As already mentioned, the subject matter of the messages exchanged in these online communities, as well as their conceptual framework, confirm Benedict Anderson’s definition of the imagined community:

It [the community] is imagined because the members of even the smallest nation will never know most of their fellowmembers, meet them, or even hear of them, yet in the minds of each lives the image of their communion.[8]

According to Anderson, regardless of the actual inequality and exploitation that may prevail in it, the imagined community is always conceived as a deep, horizontal comradeship.

[9] The participants in the online Sephardi interactions are indeed forming an imagined community, in which a comradeship that cannot possibly be reached offline is created Another illuminating context to the phenomenon we are looking at is Jean Amery’s interpretation of the concept of the transportable homeland: [10]If I am permitted … to give an answer to the question how much home does a person need, I would say: all the more, the less of it he can carry with him. For there is, after all, something like a transportable home[land], [11] or at least an ersatz for home. That can be religion, like the Jewish one. [12]

Pierre Nora’s description of the cultural stage in which, when “lieux de mémoire” no longer exist, “milieux de mémoire” are created provides a most relevant approach to the situation we are looking at. [13]

The online imagined community as a milieu de mémoire cannot be understood without taking into consideration another key concept. Describing the social network developing on the web, Howard Rheingold started a pioneering discussion of the virtual community:

My seven-year-old daughter knows that her father congregates with a family of invisible friends who seem to gather in his computer. Sometimes he talks to them, even if nobody else can see them. And she knows that these invisible friends side of the planet. [14]

Bearing these various theoretical concepts in mind, the understanding of the online reconstruction of Sephardi life and identity as well as the personal and collective memory based on a culture that has a minor functionin today’s offline world becomes clear.

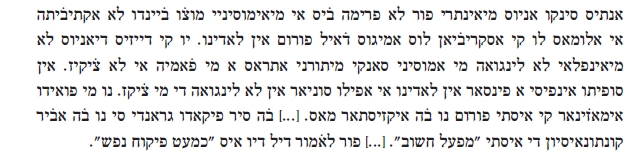

The following message, posted on Tapuz in February 2009 by ofer ashkenazi is motivated by de wish to revive the Sepahrdi culture and JS language, whose offline existence is endangered. All the abovementioned theoretical insights function as a context for it: [15]

komo tengo diskarino a ladino avlantes!!! Me akodro ke [kuando] era chiko todos avlavan espaniol in la kaya (me engrandesi in Yaffo) era muy ermozo, toda esta ermoza kultura eskapo. Komo kero ke toda la jente de la Turkiya e la Grecia van a alevantar de la foya e van a kidar kon mozos. Kyeriya murir kon eyos, yo sto ke no tengo qualo azer in la vida sin eyos. Eyos eran me alma. tanto treste ke pekado. Me swenyo ez estar kon eyos por un dia sola para nostaljia. Quando gritan Nissim ya basta. Ach ke swenio.!!!!!!!

[How I long for Ladino speakers!!! I remember that [when] I was little everybody spoke Spanish in the street (I grew up in Jaffa.) It was very beautiful. All this beautiful culture ended. How I wish that all the people from Turkey and Greece get up from the grave and stay with us. I wish I died with them, I am the one who has nothing to do in this life without them. They were my soul. So sad what a sin. My dream is to be with them for just one day for the nostalgia. When they shout Nissin that’s enough, ah what a dream!!!!!!]

Recently, the Tapuz Ladino Culture Forum’s founder and moderator announced that she can no longer act as the group’s leading figure, an announcement that evoked many emotional reactions. One of this reactions, posted by Trandafilo in November 2009, demonstrates the process of personal and collective JS and Sephardi revival that in our times may take place only online:

Five years ego I entered for the first time and was very excited to see the activity and more than that what the friends of the Ladino forum are writing. I, who have not used the language for years [decades?] got very excited because I returned to my family and the childhood. All of a sudden I started to think in Ladino and even dream in the language of my childhood. I cannot imagine that this forum is not going to exist anymore […] It will be a big sin not to have a continuation of this » mif’al hashuv» (important enterprise.) … For the love of God this is “kimat piku’ah nefesh»(almost a matter of life and death.)]

Realizing that the exciting theory is not sufficient for a complete the JS online communities, I propose adding to it a new concept that may lead to an improved description and analysis of the phenomenon.

The People Who Almost Forgot: JudeoSpanish Online Communities As a Digital Home-Land – Part 2

The People Who Almost Forgot: JudeoSpanish Online Communities As a Digital Home-Land – Part 3

——————————————————————————————————————

[1] JudeoSpanish is mainly a Romance language with embedded Hebrew, Aramaic, Arabic, Turkish and Balkan components. Originating in medieval Spain, it became widespread Jewish language, when the descendants of Jews expelled from the Iberian Peninsula in 1492 continued to use it in oral and written form in their newly established communities in the Ottoman Empire and Northern Morocco. The language received various names down the centuries, including the term, “Ladino”, which originally referred to the JudeoSpanish dialect used in the translation of the Bible and other sacred Jewish texts since the sixteenth century. This dialect differs from the spoken and written language used by sephardi Jews. The language used by the participants in the online Sephardi correspondence circles analyzed in this paper is thus referred to as “JudeoSpanish” (and in short “JS”), and the culture it represents is referred to as “Sephardi”. The term “Ladino” is used only when quoted directly from those websites dealt with in this discussion. [2] Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, Verso, London 1983. [3] For more about the social online interaction at stake, see David Crystal, Language and the Internet, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2001, “The language of chatgroups”, pp. 129170. [4] http://groups.yahoo.com/group/Ladinokomunita/. For a forthcoming discussion of this group, see Marcy BrinkDanan, “Limiting Ladinoland: Virtuality and Ideology in an Online Speech Community”. [5] http://www.tapuz.co.il/tapuzforum/main/forumpage/asp?forum=420/. [6] Naturally, webbased activities are constantly changing and cannot possibly be grasped in their entirety. The digital fieldwork done as basis for the present study was concluded in August 2009, before the research was first presendted. The data collected in it is analyzed in retrospect, not without a realization that possible changes may have occurred in it ever since then. [7] Radhika Gajjala, “Cyberethnography: Reading South Asian digital diasporas”, in Kyra Landzelius (ed.), Native on the Net: Indigenous and Diasporic Peoples in the Virtual Age, Routledge, London & New York, 2006, p, 273 [8] See Note 2, p.6. [9] See Note 2, p.7. [10] Heinrich Heine originally presented the concept of the portable homeland. For hisconsideration of the Jewish Portable Fatherland, see Henryk Broder, A Jew in the New Germany, translated from the German by the Broder Translators’ Collective, edited by Sander L. Gilman and Lilian M. Friedberg, University of Illinois Press, Urbana 2004, p.44. [11] Amery uses the word “Heimat” (capitalized in the German original), which refers to a homeland as well as to a home. Thus, here I am using “Homeland” in accordance with Amery’s Hebrew translation, as it seems more accurate in the context in which it appears. [12] Jean Amery, «At de Mind’s Limit: contemplations by a survivor on Auschwitz and Its realities» , translated from Germanb by Sidney Rosenfeld and Stella P. Rosenfeld, Indiana University Press, Bloomington 1980, p. 44 [13] Pierre Nora, “Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire”, Representations 26 (1989), pp. 7-25 [14] Howard Rheingold,the Virtual Community, MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass. 2000 and the Introduction to the electronic version quoted here: http://www.rheingold.com/vc/book/intro.html/. [15] Hereafter, all quotes form the online JS correspondences are given in the original script and orthographic systems used by their writers, and followed with an unedited English translation.Fuente: El Prezente – Studies in Sephardic Culture. Editors: Tamar Alezander – Yaakov Bentolila – Eliezer Papo. El Prezente, vol. 4, December 2010

eSefarad Noticias del Mundo Sefaradi

eSefarad Noticias del Mundo Sefaradi