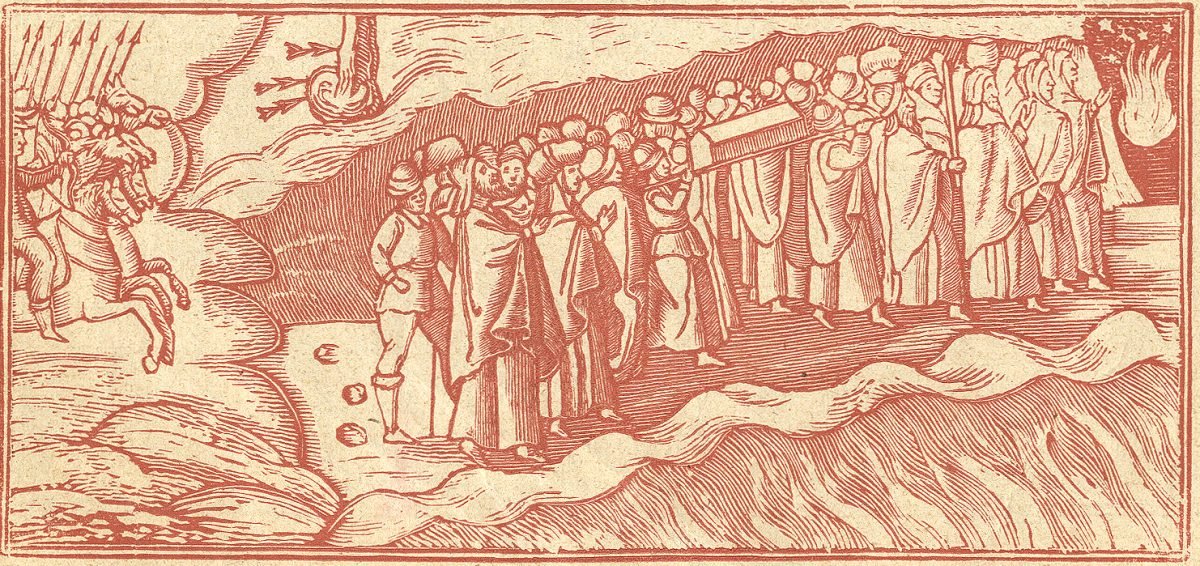

The Israelites crossing the Sea of Reeds (popularly known as the “Red Sea”) from Seder Agada shel pesah im pitron be-lashon Sefaradi. Printed in Livorno, Italy by Solomon Belforte, 1903. Courtesy of Susan Solomon

Kuando el puevlo de Yisrael d’Ayifto salieron kantando (“When the people of Israel left Egypt singing”) is a ballad, or romansa, about the Exodus that was sung in Ladino as part of the Passover Seder in homes and communities in the Ottoman Empire. Like all good ballads, it tells a gripping story, in this case of the exodus from Egypt. The ballad is particularly vivid in its poignant and dramatic descriptions of the men, women, and children, carrying the dough that would become matzah as well as gold, the lightest of their possessions. It is complete with dialogue: Moses, with his flaming staff, exhorts his fearful people to have faith, that they will not die tombless in the wild. Then, all of a sudden, God’s voice thunders down from heaven instructing Moses to lead his people across the sea, while Pharaoh and his armies, waving their red banner, are close in pursuit. We know how the story ends. The ballad ends with praises to God Almighty, King of the Universe, for his miracles.

This ballad is classified in romancero collections under the modern Spanish title of El paso del Mar Rojo (“The Crossing of the Red Sea”). Some versions begin with, “En catorze de Nisán, kuando el puevlo de Yisrael.” All versions follow the Spanish romance (ballad) format to a tee, narrating the story in 16-syllable lines with a break in the middle, with each line ending in rhyming vowels (assonant rhyme).

However, even though it copies the romance form, Kuando el puevlo de Yisrael is a uniquely Sephardic ballad. It is found nowhere in Christian Spanish ballad repertoires. It survived only among the Ottoman Sephardim and the crypto-Jews of Portugal. (For crypto-Jewish versions see Amilcar Paulo, Romanceiro criptojudaico: Subsidios para o estudo do folclore marrano, Bragança 1969, pp. 10 and 18). This suggests that the ballad had medieval origins among the Jews of Spain and Portugal, prior to the edicts of conversion and expulsion.

Another special feature of this ballad is that it was preserved and transmitted across the generations in both oral and written form. It was likely sung widely throughout the communities in the Ottoman Empire. Oral versions have been recorded from Salonica, Marmara, and some small fragments from Rhodes. Written versions can be found in manuscript books that document rituals and songs for Passover that are not part of the official Haggadah. One of these is Ne’im Zemiroth, compiled by Moses ben Michael ha-Kohen in Venice in 1702. (See I. González-Llubera, “Three Jewish Spanish Ballads in MS. British Museum Add. 26967,” Medium Aevum, (Oxford, England 1938), pp. 15-28).

Liza and Leo Azose (Azús), Seattle, WA, 1973

The singer of this version of the ballad is the late Mr. Leo Azose (1898-1990), who was a leader in Seattle’s Sephardic community and the son of Rabbi Solomon Azose. How Mr. Azose came to learn this ballad we don’t know. He may have heard it at his family’s Passover table in Marmara, then in the Ottoman Empire (in present-day Turkey), or he may have learned the verses from a written version, bringing it into his oral repertoire. Mr. Azose recorded the ballad twice. The first time in 1958, when Professors Samuel Armistead and Joseph Silverman came to record medieval Spanish ballads in Seattle; the second time for Rina Benmayor in 1973. Both times, Mr. Azose sang the identical version that can be traced to a manuscript source. (See S. G. Armistead and J. H Silverman, “Hispanic Balladry among the Sephardic Jews of the West Coast.” Western Folklore XIX (1960), 229-244).

With the diaspora and migration of Sepharadim from the Ottoman Empire to the United States and other countries, came the waning oral traditions. The Seattle Sephardic communities originating from Turkey and the island of Rhodes are unique in that these were tight enclaves where traditions have been thankfully preserved more than in other locales. Leo Azose’s version of Kuando el puevlo de Yisrael is one of the most complete in existence and we are fortunate that he recorded it.

Notes compiled by Rina Benmayor from “El Paso del Mar Rojo.” R. Benmayor, Romances judeo-españoles de Oriente, (Gredos, Spain 1979), pp. 83-87.

Sung by Mr. Leo Azose, originally from Marmara, Turkey. Recorded in Seattle June 10, 1973. Number 8a in Benmayor, Romances judeo-españoles de Oriente.

Leo Azose’s rendition of “El Paso del Mar Rojo” (Crossing the Red Sea)

(Translation reads from left to right)

When the people of Israel left Egypt singing

children and wives singing the Song of Songs

some carried the wood and others carried the dough,

the men carried the children in their arms and by the hand

the women carried the gold which is a lighter load.

Moshé turned his head to see how many were crossing,

He saw Pharaoh advancing with his red banner.

“Where have you taken us, Moshé to die in this wilderness

to die without tombs or be drowned in the sea?”

“Don’t be afraid, Jews and don’t lose hope.

Pray to Him and I will do the same.”

So many were the prayers that rose to God on High

A voice descended from heaven calling to Moshé:

“Come here Moshé, My son, do My command.

Take this staff, Moshé take this staff in your hand.

Part the sea in twelve paths and lead your people to safety.”

The Jews were crossing the Egyptians were drowning.

Only Pharaoh was left behind hanging by the neck.

Let us recognize the miracles that God on High bestows on us.

He is one and not second He is the Father of the entire world.

Translation by Rina Benmayor

El Paso del Mar Rojo. Rina Benmayor, Romances judeo-españoles de Oriente (Gredos, Spain 1979)

Dr. Rina Benmayor is Professor Emerita of Oral History, Latina/o Studies, and Literature at California State University Monterey Bay, and is author of the books Romances judeo-españoles de Oriente : nueva recolección and co-editor of Migration & Identity, Telling to Live: Latina Feminist Testimonios, and Memory, Subjectivities, and Representation: Approaches to Oral History in Latin America, Portugal, and Spain. She received her Ph.D. in Romance Languages & Literatures from UC Berkeley.

—Visit the Benmayor Collection of Sephardic Ballads, part of the digital Sephardic Studies Collection—

For Further Exploration

- Sephardic Ballads Collection Highlights by Rina Benmayor

- The Faces and Voices of Sephardic Music in Seattle, profile of Rina Benmayor’s research by Ty Alhadeff (Mar. 2014)

Fuente: This article originally appeared on jewishstudies.washington.edu, the website of the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies at the University of Washington. Reprinted here with permission.

eSefarad Noticias del Mundo Sefaradi

eSefarad Noticias del Mundo Sefaradi