What she said

“[Ladino is] a 15th century Spanish that the Jews that were expelled from Spain spoke in the 15th century when they went to other countries like Holland, Turkey, Italy, and North Africa. They kept their language to this day. The construction of the language is 15th century Spanish mixed with some Hebrew or local words. My grandmother and some aunts spoke Ladino so it was very clear that that was our cultural heritage.”

Biography

Rita Arditti is one of the three daughters of a Sephardic Jewish family that had emigrated from Turkey.As a Sephardic Jew growing up in a country that was 95% Catholic, Rita Arditti knew what it meant to be a «minority within a minority». Born in Argentina in 1934, one of the three daughters of a Sephardic Jewish family that had emigrated from Turkey, Rita was aware as a young child that, «To be a Sephardic Jew in Argentina is to be invisible.» It was, in part, that awareness of invisibility that helped to develop Rita’s political consciousness.

Under Peron’s government, the national university was closed much of the time, making it hard for students to pursue their studies. In 1952 she came to the US and attended Barnard College in New York City for one year. After that she went to the University of Rome, Italy, where she earned a Doctorate in Biology. She came to the United States in 1965 to Brandeis University with a postdoctoral fellowship to the Biochemistry Department and in 1966 moved to Cambridge. She then started a position as a Research Associate in the Department of Bacteriology and Immunology at Harvard Medical School. In the late sixties and early seventies she became involved with other socially active scientists in the group, «Science for the People,» that sought to expose the connections between science, the Vietnam War, and politics.

After developing a course at Boston University entitled «Biology and Social Issues» in which she taught biological principles and the various ways in which they may be used in society to perpetuate inequality, she became involved with the feminist movement and co-founded, with three other women, New Words, a women’s bookstore, in Cambridge in 1974. Starting as a single room rented from a restaurant on Kirkland Street, the store expanded to include an impressive collection of books, talks, and lectures, in a new location on Hampshire Street, contributing to build a strong community of women and to participation in civic dialogue. After 28 years of operation, the New Words bookstore was eventually transformed into the Center for New Words, its mission being to «use the power and creativity of words and ideas to strengthen the voice of progressive and marginalized women in society.» It is currently located at the YWCA building on Temple Street in Central Square, Cambridge.

While researching genetics at Brandeis University and later at Harvard, Rita helped found two activist groups: Science for the People, and the Women’s Community Cancer Project.

In the 1980’s Rita’s interest in the intersection of science and politics moved to the human rights arena when she agreed to translate for a Boston tour of the grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo. Rita was moved by the women’s search for grandchildren who had disappeared under Argentina’s military dictatorship from 1976-83.

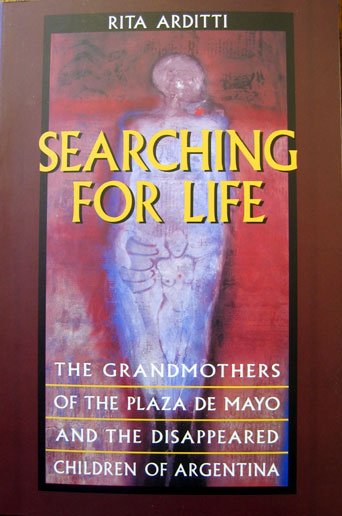

During annual visits to Argentina, Rita decided to write a book about their struggle to find children who might be living under assumed identities. With the publication of Searching for Life: The Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo and the Disappeared Children of Argentina, the story of the missing became an international one. The first in depth study of the grandmother’s work, Searching for Life helped to publicize a quest that was often fraught with danger. In 2001 the grandmothers were nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize. Rita’s book was part of the supporting documentation offered for that nomination.

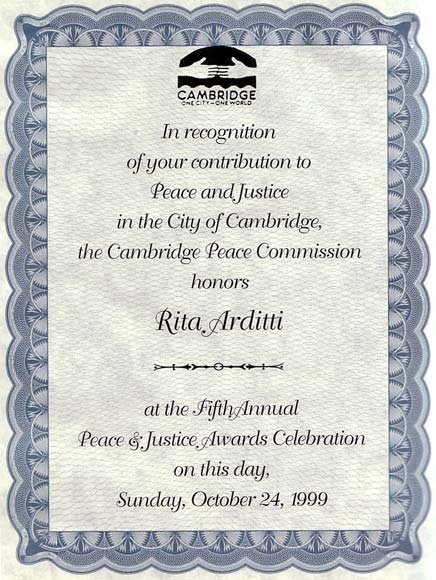

In 1994, she was the recipient of a Jessie Bernard Wise Women Award from the Center for Women Policy Studies in Washington, DC, and in 1999 she received the Peace and Justice Award from the City of Cambridge, MA. In 2005, she was chosen to be one of the «Women Who Dared» from the Jewish Women’s Archive. She was an Emeritus faculty member of the Union Institute and University where she taught for 30 years..

More about What she said

“[Ladino is] a 15th century Spanish that the Jews that were expelled from Spain spoke in the 15th century when they went to other countries like Holland, Turkey, Italy, and North Africa. They kept their language to this day. The construction of the language is 15th century Spanish mixed with some Hebrew or local words. My grandmother and some aunts spoke Ladino so it was very clear that that was our cultural heritage.”

“I also had an aunt who was a role model in a way because she was sort of eccentric and made me feel that you could do anything. She was a little bit unreal, but she was a role model. And then of course when I become a feminist and I started to read about the early feminists, the Suffrage Movement, that was so inspiring the fact that women would take up such big projects. I also think of who has helped me understand things and inspired me like Adrienne Rich and Gerda Lerner.”

“I think for me when I started looking at my own life — patronizing attitudes from men, and the lack of respect and support and recognition — it all felt very familiar, it felt like being a Sephardic Jew as a child again. So as a woman in science, I realized that I wanted to do something that would be broader than just the research. I couldn’t just care about women in science — the problem was much larger. The more I read and analyzed my own experience, I had to become an activist, there was no way out for me.”

“But in doing so [the Grandmothers and Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo] transformed the role completely because they became so public and they challenged the separation between the traditional and the public role of women showing that what is called traditional is also a public issue. Caring for your children was something they were doing, but that is something that everyone should be doing. What was called public was deficient in not incorporating that dimension of caring that they brought. So they started as very traditional — mothers and housewives — but in the process of fighting for the recognition of the traditional role, they transcended them and they challenged that separation between the private and the public.”

“We wrote the declaration for the rights of women in science, which was in our magazine, and we published a book entitled Science and Liberation. I was part of a group that put together a booklet that was called «How Harvard Rules Women» in 1977 which showed how Harvard was a patriarchal institution and how women were relegated to secondary and marginal roles. My writing has always focused on women, women and health, particularly cancer, women and reproduction, and women and human rights. Locally, I am one of the four women who co-“founded New Words bookstore in 1974, in Cambridge, one of the first women’s bookstores in the country. I am now a member of the Board of the Center for New Words, a new non-profit organization whose mission is summarized by our slogan, «Where Women’s Words Count.» We recently held our second annual conference on Women and the Media, WAM!, at the Stata Center at MIT. I have also been a member of the Board ofSojourner, the feminist Boston area monthly publication, for a number of years.””

“[It] was a very special experience because Argentina is a country that is 95 percent Catholic. The Catholic presence is very strong in the government, in schools, and in everyday life. Even now it is very strong … to be a Jew in Argentina is to be a minority, an extreme minority. But to be a Sephardic Jew is to be a minority within a minority Because Sephardic Jews usually have names that sound Greek, Italian, Spanish, or Turkish, they are not recognized as Jews in Argentina by the rest of the population. The majority of the Jews in Argentina are Ashkenazi – 80%. So when you are a minority within a minority, you have certain experiences of being marginalized or not recognized. So I think that was a big factor in my becoming a socially aware person.”

“Persistence is the key to anything. It doesn’t matter if you are young or old or super intelligent. Once you are convinced to the core of the importance of something you just keep doing it. It’s such an empowering feeling. I learned that seeing them year after year accomplish so much. It has given me a sense of empowerment that as I get older and older I can do things and I won’t give up. I’ve learned a lot and have applied it to me”

March 29, 2008 interview at lunchtime on the second day

WAM!2008 (Women, Action & the Media)

with Center for New Words Board Member, Rita Arditti.

Source: Jewish Women’s Archive. «JWA – Women Who Dared – Biography Rita Arditti.» and personal interview by Sandra Pullman, 2003 for the Cambridge Women’s Heritage Project.

eSefarad Noticias del Mundo Sefaradi

eSefarad Noticias del Mundo Sefaradi