Faced with threat of execution for Jewish observance, Sephardi conversos created the festival of Santa Esterica to replace Purim

According to tradition, around 1,900 years before the Spanish Inquisition, a baby girl named Hadassah was born in the Persian Empire. She was orphaned at a very young age and her cousin Mordechai assumed custody of her. Under his tutelage, she internalized the spark of her Jewish identity.

After a few years, an opportunity presented itself, and Mordechai placed her in King Ahasuerus’ harem. He told her that her name was now Esther.

Mordechai told Esther that she was still a Jew, but that she must not let anyone know. If she was lucky, one day she could be the queen of Persia. It is said that she was a vegetarian, to avoid eating non-kosher meat. Queen Esther seemed to be fully assimilated, yet she never forgot who she really was. She hid her Judaism, and eventually married King Ahasuerus.

When the Spanish Catholic monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella established the Spanish Inquisition in 1478, many Jews converted to Catholicism outwardly. Inwardly, they kept practicing Judaism in secret, becoming anusim, conversos, or crypto-Jews.

Queen Esther was an inspiration to the anusim in that she modeled a way for them to remember and retain their true, hidden Jewish identity while integrating into the society around them. The conversos implemented a strategy to be able to continue practicing Jewish customs while hiding their observance by inserting a Jewish tradition into a Catholic practice or “syncretism” — the mixing of rituals from different religions.

When the Roman Catholic Church formally recognizes a person as a saint, this person is canonized. A person who has not been canonized may, however, still be referred to as a saint if it is believed that they are “completely perfect in holiness.” The crypto-Jews took advantage of this loophole.

Although Queen Esther was not canonized by the Catholic Church, the anusim transformed her into Saint Esther. They called her Santa Ester or Santa Esterica. They were able to continue honoring Purim by reinventing it as “The Festival of Saint Esther.”

The Festival of Saint Esther originated in Spain. When Spain issued the Edict of Expulsion in 1492, many Jews and conversos escaped to Portugal, taking their traditions with them. Their respite was short-lived and in 1497 the Portuguese king Manuel I married Princess Isabella, the daughter of the Spanish Monarchs Isabella and Ferdinand. A clause in this marriage contract extended the Spanish expulsion to Portugal, ousting the Jews once more.

The New World beckoned as a safe haven and the Spanish and Portuguese anusim were among the first settlers in the territories controlled by Spain in what is now Mexico. The Spanish Inquisition followed them to Mexico, however, pushing the conversos north.

The establishment of Nuevo León in the American Southwest is notable in that it was almost entirely carried out by crypto-Jews. Luis Carvajal y de la Cueva, a Portuguese converso, received a royal charter to settle this land without religious scrutiny of the pioneers who followed him. The Festival of Saint Esther was disseminated in the New World by these conversos. It was generally the women of the family who maintained this tradition.

The Festival of Saint Esther had two parts. The first part of the holiday was called the Fast of Queen Esther. The women fasted for three days. This fast replicated the fast Queen Esther asked of Mordechai and the Jews of Shushan before she approached King Ahasuerus.

It was too risky to celebrate the Festival of Saint Esther publicly. This was because the Spanish Inquisition considered such an activity to be Judaizing, or the adoption of Jewish beliefs. However, the archives of Mexico’s Inquisition retain testimony about this fast.

In 1643, Gabriel de Granada confessed that in his family, the women divided up the fast between them. Each would fast for one day. The punishment meted out by the tribunal of the Inquisition for Judaizing was “relaxation,” which meant burning at the stake.

Fasting had a special significance for the forced converts. In “The Fast of Esther in the Lore of the Marranos,” Moshe Orfali explains that the conversos felt that they lived in a constant state of sin. Fasting helped them atone.

The second, celebratory part of the festival was the Feast of Saint Esther. In her article “Women, Ritual, and Secrecy: The Creation of the Crypto-Jewish Culture,” Janet Liebman Jacobs relates that the women lit devotional candles in honor of Saint Esther. It was an occasion of mothers bonding with their daughters. They cooked a banquet together. The mothers took advantage of this opportunity to teach their daughters special family recipes that adhered to the remembered laws of kashrut.

The festive, public Purim celebration was transformed into a private meal held at home. As a result, many Jewish traditions were transmitted from mother to daughter.

The crypto-Jews also had their own special way of honoring Esther year round by enshrining her in a piece of art.

All Spanish colonies had a special type of religious art form called santo. Santos were statues made of wood or ivory which depicted the Virgin Mary, saints, or angels. In Latin America and the American Southwest, these statues were called bultos. The bultos were carved from wood, and then coated with a mixture of glue and gypsum, called gesso. They were then painted with vivid homemade pigments.

In crypto-Jewish homes, Queen Esther was fashioned into an icon and transformed into a bulto of Saint Esther.

Santo art was also expressed as devotional paintings called retablos. Traditionally, these were executed on sheets of metal such as copper or tin. Since there was a shortage of metal in the New World, the retablos were made of wood. Like the bultos, they were coated with gesso and painted. The paints were made from natural materials such as plants, insects, ash, and clay. Then they were varnished with tree resins. Crypto-Jews also commissioned retablos of Saint Esther.

It is less common to find bultos or retablos of Saint Esther in the American Southwest today. This is the legacy of Archbishop Peter Davis, who was the Archbishop of Santa Fe from 1964 to 1974. According to Jacobs, the archbishop wanted to get rid of all the Jewish rituals in New Mexico. He told his parishioners that there is no Saint Esther in Catholicism. and explained that the celebration of Esther is called Purim, and that Purim is part of the Jewish faith.

Despite Davis’ best efforts, it is still possible to find bultos and retablos of Saint Esther in crypto-Jewish homes today. In “The Book of Esther in Modern Research,” by Leonard Greenspoon and Sidnie White Crawford, for example, Santa Ester is portrayed as holding “a hanging-rope in one hand, and a crown in the other, weighing the danger of execution against the safety of royal immunity.”

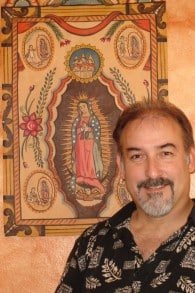

There are also contemporary artists creating icons of Saint Esther. Charles Carrillo is one of New Mexico’s most prominent santeros, or artists that carve and paint saints. Carrillo earned a doctorate in archaeology from the University of New Mexico. While working on a dig, he became inspired by the work of the santeros. He conducted a lot of research, and became a self-taught artist whose mission is to preserve the homemade materials, techniques, and designs of the master santeros of 18th century colonial New Mexico. In 2006 he was awarded the National Endowment for the Arts National Heritage Award

According to Carrillo there is a large community of crypto-Jews in New Mexico.

“They came here in the 1500s,” he told me. “I haven’t done one in a long time, but sometimes I still get a commission to create a Santa Ester.” There is an old saying in New Mexico, “A cada santo llega su función,” meaning that there is a saint for every occasion.

“My Santa Ester always has dark hair,” Carrillo said. “It’s a New Mexico tradition. I want my artwork to reflect her attributes. Esther means ‘Hadassah’ in Hebrew. Hadas is a myrtle or fragrant plant,” he explained.

In Carrillo’s retablo, Santa Ester is wearing a crown adorned with myrtle. She holds a myrtle branch in one hand. The rosette at the top of the retablo is decorated with myrtle branches. Santa Ester holds a scepter in her other hand that marks her as a queen. Her scepter is decorated with a pomegranate, an ancient Jewish symbol of fertility, promise, and fulfillment.

The red curtains framing Santa Ester are traditional in a New Mexico retablo. They are an allusion to a stage and symbolize that this has been revealed to us, and that we had better pay attention before the curtains close.

The Spanish Inquisition was formally ended in 1834. It is rational to believe that crypto-Judaism was something that existed in the past and is no longer occurring. However, it has persisted, and there are many anusim that continue their secret practices to this day while living in Spain, Portugal, Italy, Latin America, and the American Southwest.

Several organizations have been established in recent years to help anusim conduct research about their family background. Name Your Roots was formed in Israel by a group of academics who hope to help facilitate research into converso family names and customs. Shavei Israel, was created to assist those descendants of Jews who wish to return to Judaism.

I wondered what it feels like for a devout Catholic like Carrillo to create an icon that he knows is for crypto-Judaic purposes. “I am honored to be asked,” he said. “Ultimately, we all believe in the same God. It is my tradition to paint the images so the story may be told.”

March 16, 2014

Source: Time of Israel

eSefarad Noticias del Mundo Sefaradi

eSefarad Noticias del Mundo Sefaradi