The Autoridad Nasionala del Ladino (National Authority for Ladino) has scored a hit with three new lavishly illustrated Ladino/Hebrew books.

The three books reviewed below, which appeal to different audiences, are part of the organization’s goals to “to promote the publication of literary and artistic works of the popular Ladino culture and the written culture in their original and in Hebrew translations.”

Created by the Knesset in March 1996, the organization also seeks “to promote and preserve the institutions that deal with the culture of Ladino” and foster the teaching of the language at the university level.

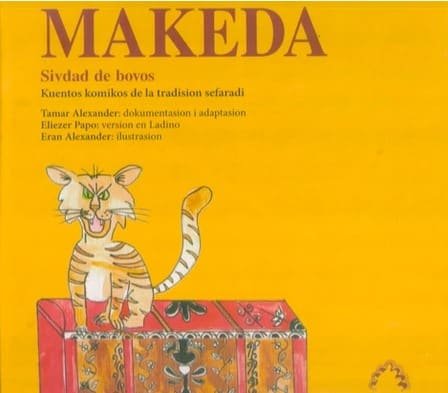

Makeda, sivdad de bovos. Kuentos komikos de la tradision sefaradi. Tamar Alexander: Dokumentasion i adaptasion. Eliezer Papo: Version en ladino. Eran Alexander. Ilustrasion: Yerushalayim. 75 p.

Makeda, sivdad de bovos. Kuentos komikos de la tradision sefaradi. Tamar Alexander: Dokumentasion i adaptasion. Eliezer Papo: Version en ladino. Eran Alexander. Ilustrasion: Yerushalayim. 75 p.

The 15 tales that make up this book are deliciously funny, told to Alexander, Director of the Authority and professor emerita of Ben Gurion University in the Negev, and other researchers by informants from Monastir (former Yugoslavia), Italy, Morocco, Turkey, Greece and Israel.

History records two cities with similar names, although spelled differently. One, Maqueda, is a small town in Castile, in central Spain. The other, Makeda, was conquered by Joshua and mentioned in the biblical book of the same name (10: 10, 28).

Historians differ as to the founding of the cities given the similarity of the names.The medieval commentator Isaac Abravanel said that the Castilian city was founded by Jews from Makeda exiled by Nebuchadnezzar. The 15th century Spanish rabbi Moses Arragel, who lived in Maqueda, asserted, on the other hands, that the Israelite Makeda has been founded by the king of Maqueda.

Alexander refers to an imaginary Makeda (Maceda, in Ladino) that has a special place in Sefardic humor, where common sense and intelligence are a rare commodity. To los makedanos, its residents, the solution to a simple problem—such as bowing the head when a door is too low or shooing a cat sitting on a trunk—is considered too complicated.

In “La nieve blanka” (White Snow), for example, it snows for the first time in Makeda, which amazes the city’s residents as they have never seen the phenomenon. Their main concern, however, is how the shamash (sexton) of the synagogue will be able to walk on the streets summoning people to attend prayers without dirtying the whiteness of the snow with his shoes. They come up with a solution that defies logic.

Most of the tales follow a pattern: a problem appears and then a solution is found. But the person who comes up with the solution is usually an outsider, who charges Makeda residents a lot of money for something that should be free—and simple.

Although the book is intended for young readers, it can be enjoyed by adults who want to practice or learn Ladino and Hebrew. The Hebrew version is presented in facing pages with vowels.

Illustrated by the author’s son with eye-catching and full-page drawings, this large-format book is the first-ever compilation of tales about Makeda, which are few. The title means, “Makeda, City of Fools. Humorous Tales from the Sefardic Tradition.”

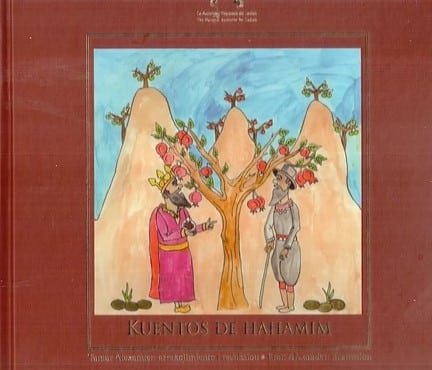

Del lejendero sefaradi: Kuentos de Hahamim de la tradision eskrita i oral de ladino avlantes. Tamar Alexander: Arrekojimiento i redaksion. Eran Alexander: Ilustrasion. Yerushalayim. 125 p.

Del lejendero sefaradi: Kuentos de Hahamim de la tradision eskrita i oral de ladino avlantes. Tamar Alexander: Arrekojimiento i redaksion. Eran Alexander: Ilustrasion. Yerushalayim. 125 p.

Alexander has done an excellent job compiling 30 tales of famous Sefardic rabbis and lesser known characters in Sefardic history.

Loosely translated, the title means, “Sefardic Legends: Tales of Wise Men from the Ladino Oral and Written Tradition.”

The tales are arranged in six chapters, called gates, each containing five stories. The first four include stories about rabbi Itzhak Luria Ashkenazi, the Ari; rabbi Moshe ben Nachman, Ramban; rabbi Moshe ben Maimon, Rambam; rabbi Abraham ibn Ezra; and rabbo Yehuda Halevi. The introduction to each gate is accompanied by a full-page photo and a biographical sketch. Rabbi Shlomo ibn Gabirol is the fourth gate.

Even though they all lived during the Middle Ages, five of them in Spain, the lessons we learn from their stories are relevant today.

The sixth chapter is devoted to four rabbis and a woman, Sol Hachuel, who played significant roles in modern in the history of Jerusalem, Turkey and Morocco. Born in 1817 in Tanger, in the northern part of the latter, Sol was decapitated in 1834 when she refused to convert to Islam. Her story is told in Haketia, a language from northern Morocco that mixes Spanish, Hebrew, and Arabic.

Another fascinating story, “Levaya i enteramiento” (Funeral and Burial), tells why Tiberias was chosen to be Rambam’s burial place.

Upon his death in Egypt, the three holiest cities in Eretz Israel began to argue about which one would have the honor to be his final resting place. Said Yerushalyim: “I am the center of the world and the Temple existed and will exist in me.”

Said then Hebron: “The fathers and mothers of the Jewish people all dwell in me. His place is in Maarat Hamachpela” (The Cave of the Patriarchs). Safed spoke last: “Who is for us the greatest since the closing of the Scriptures but rabbi Shimon bar Yohay? The Rambam’s grave should be next to this tzadik on Mount Meron.”

The leaders of Tiberias remained silent. After thinking about the matter, they put the Rambam’s body on a camel and agreed that his burial place would be where the animal knelt. A large multitude followed it north for several days and upon reaching the entrance of Tiberias (“the most modest of the cities, which didn’t ask anything for itself”), the camel knelt.

Culled from 30 Hebrew journals and books, these tales are to be treasured for years to come. Alexander was assisted by a team of researchers. The Hebrew version is presented in facing pages without vowels.

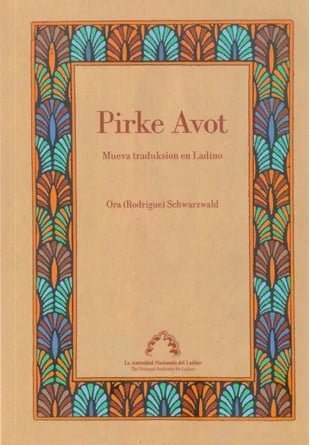

Pirke Avot: Mueva traduksion en ladino. Ora (Rodrigue) Schwarzwald, Yerushalayim. 96 p.

Pirke Avot: Mueva traduksion en ladino. Ora (Rodrigue) Schwarzwald, Yerushalayim. 96 p.

Rodrigue Schwarzwald, President of the National Ladino Academy in Israel and professor emerita of Hebrew and Semitic Languages at Bar-Ilan University, has made a great contribution to the field of Sefardic religious literature with this easy-to-read translation.

In this edition the text is presented in three formats: Ladino in Roman characters, Ladino in Hebrew characters and in Hebrew without vowels.

The separation between chapters is illustrated with facsimiles of the title page of Pirke Avot editions printed in Jerusalem, Tel Aviv, Venice, Florence and Livorno (Italy), Portugal and Salonika (Greece), some as old as 1495.

Rendered in English as «Ethics of the Fathers” or «Chapters of the Fathers,» this tractate of the Mishna is immensely popular for its focus on Jewish values and ethics. In some Jewish communities it’s customary to study its six chapters on the six Shabbats between Passover and Shavuot.

Fuente: Daniel Santacruz – kolsefardim.net

eSefarad Noticias del Mundo Sefaradi

eSefarad Noticias del Mundo Sefaradi