By Josh Nathan-Kazis  Madrid

Madrid

The Spanish government expelled the Jews in 1492. In 2012, they said that they wanted us back. At a press conference that November, two ministers announced that any Sephardic Jew who wanted a Spanish passport could have one. Then nothing happened. By late 2013, Spain had not given out any passports. No one even knew how to apply. I’ve got a little bit of Sephardic blood, and my grandfather looked like a duke in an El Greco painting. So, at the end of 2013 I went to Madrid to see about becoming Spanish, and to figure out what Spain wanted with us after 520 years.

Part 1: ‘Never Return’

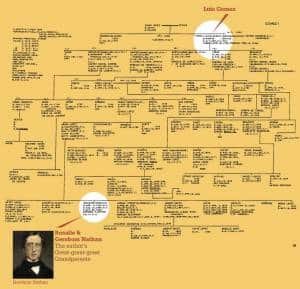

On a Friday afternoon in early November, I spread out four sheets of paper on the glass conference table at Spain’s official Jewish federation and launched into my bid for Spanish citizenship. I pointed to the name Luis Gomez at the top of one of the pages, a copy from a huge book of genealogies that my grandmother keeps in her dining room. Gomez, born in Madrid in 1660, was my great-great-great-great-great-great-great grandfather. He died in New York City; a house he built upstate is now a museum. I hadn’t brought a photo of the house. All I had to show to María Royo, the spokeswoman for the Jewish federation, was this family tree.

When the Spanish ministers announced that they would offer citizenship to Sephardic Jews, they told the press that the actual decisions about which Sephardim would qualify for Spanish passports would be made by the Spanish Jewish federation, the Federación de Comunidades Judías de España. What the ministers didn’t say was exactly how the Federación was supposed to decide who was Sephardic and who wasn’t. “So, if I had this, this would be enough?” I asked Royo in Spanish, gesturing vaguely at the generations of Nathans and Gomezes in front of us. She did not seem impressed. “This is just a piece of paper,” Royo said. This was going to be harder than I had thought.

•

Becoming Spanish had started to sound fun at a family barbeque in August. I brought up the citizenship offer over gin and tonics before dinner. We instigated half-serious plans while my dad overcooked the burgers: Why not apply for passports? Why not do it en masse? Why not organize a delegation and see if we can get the Spanish king to deliver a formal apology?

I imagined a dozen Nathans in top hats and tails, Juan Carlos tapping our shoulders with a sword, his wife Sofía dealing stiff new passports from a deck.

The Nathan name has rated us special treatment before. Our ancestors were among the first Jews to settle in New Amsterdam in the 17th century, and we’ve made a lot of the connection. We have been interviewed for documentaries about the history of Jews in America; there’s a pulpy book about our set of early American Sephardic families. (Actual chapter title: “‘Nathans Don’t Cheat’ — But Do They Kill?”) My uncle just finished a term as president of Shearith Israel, the Sephardic Manhattan synagogue our family has attended for some 350 years; my grandfather and great-grandfather were also presidents.

Citizenship, however, has deeper implications than a good seat in synagogue. I worried about its implications for my historic guilt quotient. Would a Spanish passport make me responsible for Columbus and the conquistadors and that whole thing with Cortés pouring gold down Montezuma’s throat? What about the sinking of the Maine? The murder of Lorca? Bullfighting?

Others took the whole thing more seriously. “I think they lost their claim to me when they kicked me out the first time,” said my 20-year-old cousin Jonathan, a junior at the University of Chicago, when we talked about it later.

Jews arrived in Spain under Roman rule and lived there under Muslim and Catholic kings for a millennium. In 1390, anti-Jewish riots started a wave of exile and conversion that culminated in 1492, when Isabella and Ferdinand expelled all the Jews who were left. They signed the order at their newly captured castle in Granada.

“[W]e, with the counsel and advice of prelates, great noblemen of our kingdoms, and other persons of learning and wisdom of our Council,” they wrote, “resolve to order the said Jews and Jewesses of our kingdoms to depart and never to return.”

As many as a quarter million split. (This figure comes from Encyclopedia Judaica; estimates vary.) Some went to Portugal, which expelled them six years later. Most of the exiles moved on to the lands of the Ottoman Empire, to Istanbul and Salonika. Others went to Morocco and Syria and Tunisia, to Egypt and Amsterdam and beyond.

Tens of thousands of others converted to Catholicism and stayed. The Church spent the next 342 years trying to weed out the insincere Catholics among them, inventively torturing suspected heretics and handing over the irredeemable to the state to be burned alive. No one knows how many Jews converted, though the number burnt as late as the 18th century — over a thousand after a secret synagogue was discovered in Madrid in 1720 — suggests that the original population of conversos must have been huge.

Openly practicing Jews didn’t return to Spain in large numbers until the late 1950s, when Moroccan independence led tens of thousands to move north across the Mediterranean. When the Moroccans opened their first Sephardic synagogue in Madrid in 1968, Spain’s fascist government marked the occasion by issuing an official order revoking the edict of expulsion, which was nice of them.

It was presumably in repentance for all of this that Spain’s justice minister and interior minister sat down at the press conference in November 2012 with the president of the country’s Jewish community to offer passports to the descendants of the expelled “Jews and Jewesses.”

We were pretty confident we could qualify. Sure, my brother and my cousins and I only have one Sephardic great-grandparent. And I don’t attend a Sephardic synagogue. (I grew up at a Conservative synagogue nearby; the sex-segregated seating at Shearith Israel didn’t work for us.) And no one in our family has spoken Ladino since — who knows? The 15th century?

Still, we’re Nathans. Nathans are Sephardic. Who was going to tell us otherwise?

There was something off-putting, though, about the way Spain’s consul general in New York talked to me about the passports.

I had gone to meet Don Juan Ramón Martínez Salazar in his office around the corner from Bloomingdales in Midtown Manhattan to see if I could learn anything about the status of the law. This was just a week before my trip. A life-sized portrait of Spain’s elderly king flanked his office door. I sat in a fancy chair and worried about staining it with my pen. The consul general couldn’t tell me much about the status of the law, but he did speak to the rationale.

Martínez did not expect that American Jews would actually move to Spain. Though he didn’t explicitly mention the economic crisis that has sapped the country of jobs, capital and political stability, the implication was clear: You would have to be crazy to move to Madrid right now. Instead, Martínez said, the passports would be a symbolic gesture demonstrating the Sephardic connection to Spain.

“This Sephardic population belongs to Spain, somehow,” Martínez told me. “It would be a good thing to, in a way, have them back.”

‘They lost their claim to me when they kicked me out the first time.’

That we belonged to Spain was news to me. For my family, to be Sephardic is to belong to America. One Nathan helped bankroll the Revolution. In the gilded age, the Nathans and their cousins were the sorts of Jews who the WASPs allowed into their social clubs while the arriviste Germans were still locked out. A Nathan lived next door to Edith Wharton. (He was later murdered spectacularly, perhaps by his son.) A cousin, Benjamin Nathan Cardozo, was a United States Supreme Court justice.

And it wasn’t just that we became American. We also cultivated a resentment of the Spanish. Emma Lazarus, who wrote the poem on the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty, was a first cousin of my great-great-grandfather. Besides paeans to America, she wrote a couple of poems that read as anti-Spanish diatribes. In “Don Pedrillo” and “Fra Pedro,” two poems in a series Lazarus wrote in 1876, she imagines an evil half-Jewish Spanish priest who looks like the devil and delivers wonderfully cruel anti-Semitic speeches: “All your tribe offend my senses/They’re an eyesore to my vision/And a stench unto my nostrils.”

Lazarus’s bile aside, I had warm enough feelings for Spain. The idea that Spain wanted to make contact with me was exciting. It pandered to my pride in our Sephardic blood and what I had always imagined to be our highborn pre-Inquisition past. I didn’t know why Martínez’s government was interested in the contact. I figured it had to do with some mix of tourism dollars and historical guilt. That sounded like a fair swap for a passport.

My editors raised the limit on my Forward credit card. I flew to Madrid.

November 2013 was a particularly bad time to try to get Spanish citizenship. Madrid was suffocating amidst endless recession, and the Jewish community there was dying along with it. The country, meanwhile, was trying to negotiate its newfound interest in its Sephardic past while figuring out how to capitalize on it. My theory about why Spain had extended the citizenship offer turned out to be more or less correct. What I didn’t expect was that my trip to Spain would undermine my own belief in those imagined highborn roots. By the time I got on the flight back to JFK, I wasn’t sure I was Sephardic anymore, and I was certain I didn’t want to be Spanish.

Fuente: http://m.forward.com

eSefarad Noticias del Mundo Sefaradi

eSefarad Noticias del Mundo Sefaradi