By Josh Nathan-Kazis

Part 10: ‘Yo El Rey’

One night while walking home in Toledo’s ancient judería, Carmen Gomez Gomez noticed something on the side of a building she had never seen before. At around eye-level, deep in the red brick, there was a series of connected lines gouged deep into the rock. An ancient Arabic inscription, she decided.

To me, when we turned up the narrow alley to look, they looked like random scratches. To Gomez (no relation, I don’t think?), they were another sign that Toledo is magical. Sometimes, when she’s falling asleep, Gomez imagines a “Midnight in Paris” scenario happening to her on the streets here, but instead of F. Scott and Zelda and Hemingway she would meet Samuel Halevy Abulafia, the Jewish royal treasurer executed by his boyhood friend King Peter the Cruel in 1360.

After Lucena, I needed some magic. I had taken a bus from Lucena back to Córdoba the night before, slept there, then caught a pre-dawn fast train to Madrid, where I left a suitcase in a train station locker before hopping on another commuter train that got me to Toledo a little after 9 in the morning. I was starting to feel a little tired.

Gomez met me at the train station. She said she had a surprise waiting for us in the city archives. I pretended to be excited.

A 30-year-old Catholic from the northern Spanish city of Ponferrada, Gomez smokes skinny cigarettes and wears a red plaid scarf. She thinks that it’s silly that the Zara in town sells high-heeled shoes — they don’t work on the stone streets here; she’s tried.

A 30-year-old Catholic from the northern Spanish city of Ponferrada, Gomez smokes skinny cigarettes and wears a red plaid scarf. She thinks that it’s silly that the Zara in town sells high-heeled shoes — they don’t work on the stone streets here; she’s tried.

Gomez came to Toledo nearly two years ago to research her dissertation on daily life in the 15th century judería. She’s relying, ironically, on records kept by the Catholic Church, which did business with the town’s Jews before it started torturing them to death. She spends her days in the archives, reading about leases of church land to families with names like Abenxoxen (pronounced Abenshushan) and Abulafia. She can show you the street in the Jewish quarter where each one lived.

Yet she is suitably skeptical of the Jewish sentimental gold rush. “Here in Toledo, everybody says they come from converts, and everyone has a mikveh in their basement,” she said. She dismissed the claims of one basement tourist site we visited that purported to be a former Jewish home with a mikveh as wishful thinking.

We drove from the train station in a little red car steered by Almudena Cencerrado, a tour guide and one of Gomez’s endless supply of helpful friends. The view of Toledo from a bluff across the Tagus River was enough to make me forget Córdoba entirely. The Tagus encircles the city on three sides, bordered on both banks by steep cliffs that have protected residents for 3,500 years. Catholic kings ruled Toledo from 1085 until the 16th century, when they decamped for Madrid and left the town a backwater. That slowed development and left the city still looking untouched and ancient 300 years later, when artists besotted with Romanticism came looking for inspiration in its dilapidated old streets.

After the artists came the tourists. Over a century ago, city boosters built phony old-looking stone arches in the judería to amp up the Romantic effect. They rebuilt the facade of a Catholic church that had been a synagogue before the expulsion so that it looked more like a synagogue. Toledo may be a little phony, but its phoniness is old enough to be of historic interest itself.

And it’s not all phony. Between the layers of piled-up kitsch, Gomez has an eye for the real thing. We passed through Plaza Zocodover, a busy square where an arch frames a view of the fields outside of town. “This is the square where, during the Inquisition, people were killed and burned,” Gomez said, flatly.

We stopped at an abandoned building with a boarded-up door locked with a chain and peered through the holes at stairs that Gomez said led up to an unrestored synagogue cupola. At the Museo Sefardí de Toledo, built on the site of a synagogue that was given to a Catholic order of warrior priests after the Inquisition and then rebuilt in the 19th century, she read off the engravings on recovered Jewish tombstones.

Gomez brought me to an Inquisition museum somewhat less salacious than the torture porn-filled one in Córdoba, but still upsetting. Inquisitors’ methods of tormenting suspected heretics seem to have had a distinctly sexual bent — there were all sorts of tools in the museum that destroyed the genitals of both male and female victims. I was visibly disturbed.

“It’s hard, but it’s history,” the ticket taker said on my way out.

With Cencerrado, we stopped at a church that houses El Greco’s 1586 masterpiece “The Burial of the Count of Orgaz.” Cencerrado spoke passionately about the work, and about how its upper half presages Impressionism, a movement that would not exist for another 300 years. “Only a genius can make you cry with emotion,” Cencerrado said.

I, meanwhile, was searching the faces of the nobles gathering around the count for one who looked like my grandfather, Edgar J. Nathan 3rd, who died in April. The long faces and long noses in El Greco paintings like “Portrait of an Elder Nobleman” and “The Nobleman with His Hand on His Chest”, both at the Prado in Madrid, had always reminded me of him. The black-clad lords in the painting in Toledo, with white ruffles around their necks and wrists, were of a similar type. I’m not sure whether they looked like him or whether I just wanted them to. Either way, my instinct here was the opposite of what it had been in Lucena — I wanted to feel a connection, not run away.

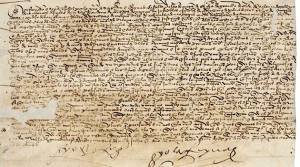

The municipal archives in Toledo are in a big library in the center of the old city. Gomez had called ahead; they were expecting us. On a table near the door were two squarish pieces of paper marked with ancient stains and creases. One, signed on June 25, 1492 in Guadalupe, just months after the order of expulsion, made synagogues and other Jewish communal property possessions of the crown. The other, signed in Córdoba on May 30, 1492, set a rapid time frame for the liquidation of Jews’ debts so they could leave the country faster.

On the back of each was the imperial seal. And on the bottom, in almost illegible scratches, were the signatures of Isabella and Ferdinand: “Yo el Rey.” “Yo la Reina.”

The orders themselves were written in a loopy Spanish script that, at first glance, looked like it should be read right-to- left like Arabic. I tried to puzzle it out: “Don Fernando e Doña Ysabel, por la gracia de dios…” The actual order of expulsion began the same way. It would have looked just like this, transcribed and signed in the same hand.

They asked if I wanted to touch the parchment. No one was wearing gloves. I dabbed at one of the ancient pages with my finger, sure I was committing a grave scholarly sin.

I left the building all turned around. In Lucena, where Sephardic Jews only existed as silhouetted joggers, the stakes had seemed lower. Everything Jewish was transparently phony, a simulacrum of something gone a millennia ago. Its incompetent abuse wasn’t something I enjoyed watching, but it didn’t feel like that big a deal.

Here in Toledo the phoniness was honest about being phony and the history felt real, and the use and abuse of the Sephardic legacy seemed to matter again. I still didn’t begrudge the Star of David-shaped cookies. But I also felt less willing to toss away my own claim.

Fuente: http://m.forward.com

eSefarad Noticias del Mundo Sefaradi

eSefarad Noticias del Mundo Sefaradi