This story has a lot of numbers, a ghastly middle, a moment of love and bravery, and a quiet, sort of happy present and ever after. It’s also superbly self indulgent because essentially you’re looking at photos from my travels. It’s like being trapped in my slideshow about my vacation. I will try not to be boring.

Recently we traveled for vacation to the island of Rhodes, in Greece. (I took a lot of pictures if you’d like to see them on Instagram.) While we were there, we visited Kahal Shalom, the oldest synagogue in Greece, and last existing synagogue in Rhodes.

At one point, there were close to 4000 Jewish people in Rhodes. Now there are less than 50. The synagogue is open as a museum, but former residents and their descendants can use the synagogue for family occasions like weddings and bar or bat mitzvahs, and for services when they visit.

So to get there, you wander around inside a medieval walled section of Rhodes, over by the actual still standing medieval castle. Just as an indication how old stuff is.

Then you turn up Simmiou street:

Note the stone cobbles on either side of the dark stone squares – they’ll be important in a minute.

When we reached the synagogue, the doors were the first thing I noticed.

Decadently stained wood with big stars of David on them – in a time where synagogues are obscuring their doors. Our current synagogue worships inside a church and our synagogue board members were asked if we wanted our logo – just the logo! – on a banner the church was commissioning.

The issue was so pressing that the board asked the entire congregation. To put a logo indicating that “Jewish people worship here” was a serious enough issue to ask the entire congregation for our opinions before making a decision.

So I’m entirely here for big stars on the door.

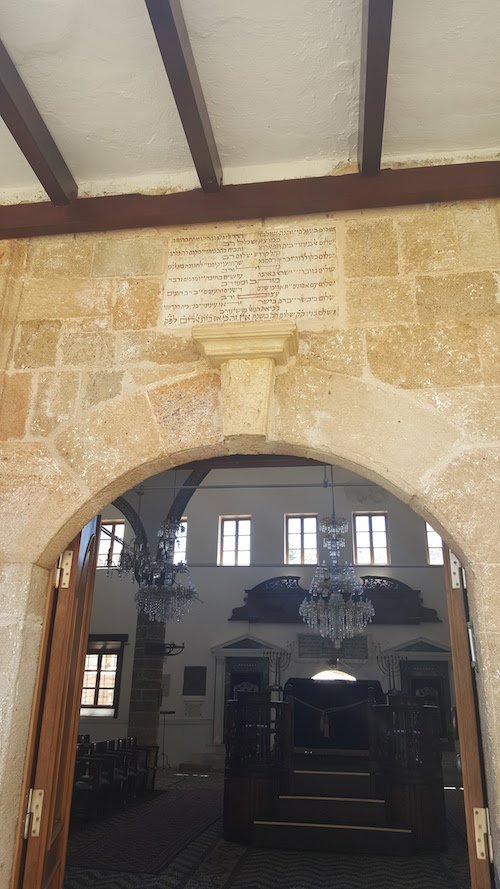

Kahal Shalom was built in 1577.

Not a typo: 1577, or 5338 in the Hebrew calendar.

It is 440 YEARS OLD. I don’t know of many things in my world that are that old, except maybe some trees.

So let’s take a tour, shall we? The building, inside and out, is constructed of pale white and light gold stone, like much of the surrounding houses and buildings. There is some carved Hebrew above the door:

I was about to go inside when this large marble plaque grabbed my attention – which is saying something because you can see in that picture the inside is pretty incredible.

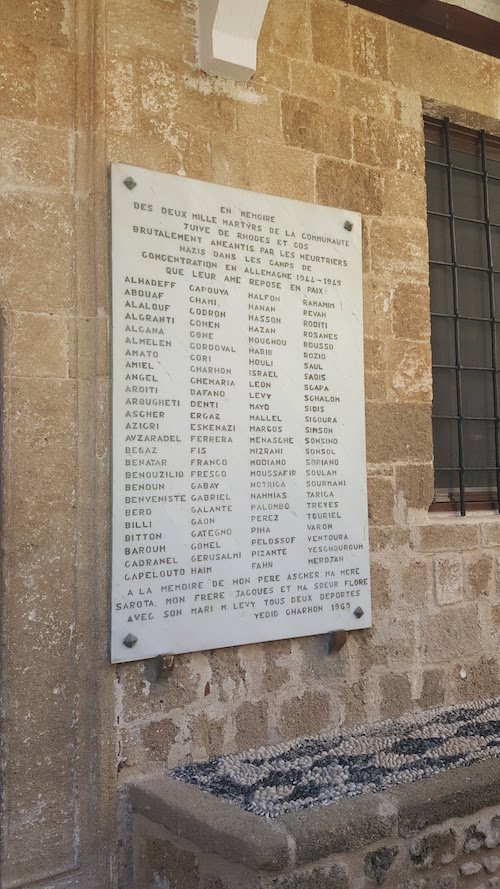

This is the list of families from Rhodes who were taken by the Nazis. A poor translation:

In memory of the two thousand martyrs of the Jewish community of Rhodes and the brutal annihilation by the murderous Nazis in the concentration camps of Germany, 1944-1945. May they rest in peace.

At the bottom of the plaque:

In memory of my father Asher, my mother Sarota, my brother Jacques, and my sister Flora with her husband Levy, all deported – Yedid Gharmon 1969

When two thousand people are taken from a community, you can’t list them all on one stone. The names on this plaque are the family names.

Note the black and white diamond pattern in the bench or sitting area below that sign. More detail on that in a moment.

Would you like to see the inside?

Looking at the bimah – the entrance is on the other side

The inside is white and light and beautiful. It’s square with a bimah in the middle in the Sephardi style, and a mechitza, or balcony area for women, was added later. The women used to worship in a separate area. From the synagogue website: “Prior to that time the women sat in rooms adjoining the south wall of the synagogue. The women’s prayer rooms (known in Ladino as ‘la azara’) viewed the sanctuary through windowed openings adorned by latticework.”

We could tell that electricity was added much after the building (obviously) and how consciously the wiring was done.

The bimah was built of carved wood in a square, with a bannister I could tell had been touched and smoothed by dozens, if not hundreds, of hands. Usually when I visit really old places (and for Americans, “really old” is almost a joke to other parts of the globe. Our “old” is Greece’s “last week,” to some extent) I think about the people who made those places, who used them, who ran their fingertips along the walls that I’m touching now. Did they know what they made would still be here? That in 2017 I’d be thinking of them, anonymous builders who made something so lasting? It’s pretty humbling.

There is a powerful quiet inside, sad and almost expectant, like there’s going to be the noise of a few hundred voices very soon, but no one shows up. Everything about this building says, in part, “We were here, and now we are not.”

When we walked in, Adam put on a kippah. I’d worn a scarf so I could cover my hair, as I wasn’t sure of the customs of the synagogue. Judging by the other women visitors, I didn’t need to bother, but I felt more respectful covering my hair, so I did. And there was a basket of scarves and shawls for women visitors next to the kippot, so I’m glad I did. (Also my scarf was very light while those were heavy fabric, and, well, if someone tells you it’s hot in Greece they are minimizing. It’s hooooot.)

After Adam covered his head, we were greeted by a woman in a blue polo shirt who asked us, “Greek? Spanish? English?” When we replied English, she smiled and handed us a page all about the museum written in English. Then we wandered around. There was another older gentleman there, also wearing a kippah and a nametag, and I asked if I could take pictures.

“No flash please!”

Later I would learn that was one of a handful of phrases he knew in English.

So check out the floor. It’s very smooth and incredible ornate….

Remember the street leading to the synagogue, and all the cobbles?

The floor inside was entirely made of big black and white pebbles.

Can you believe that?

It looks like a mix of pearls and mussel shells (which wouldn’t be in a synagogue but ok) and each one is perfectly level. I was wearing flats, but I have the magical ability to sprain my ankle even while I’m sleeping. Here, I didn’t turn my ankle at all. Not once. How do you do that? Who built the floor? How do you floor like that?!

This carving was in the wall of the bimah where the lectern was which would probably hold the Torah if it were being read.

Another bad translation (by me):

This pulpit is offered by Regine and Semah Franco in memory of the members of their family. Moishe and Mazaltou Franco, Jacov and Rosa Franco, and their children, Rachel and Aaron, Issac and Sol Franco and their children, Marie Lea and Rabina, dead in deportation in the year 1944.

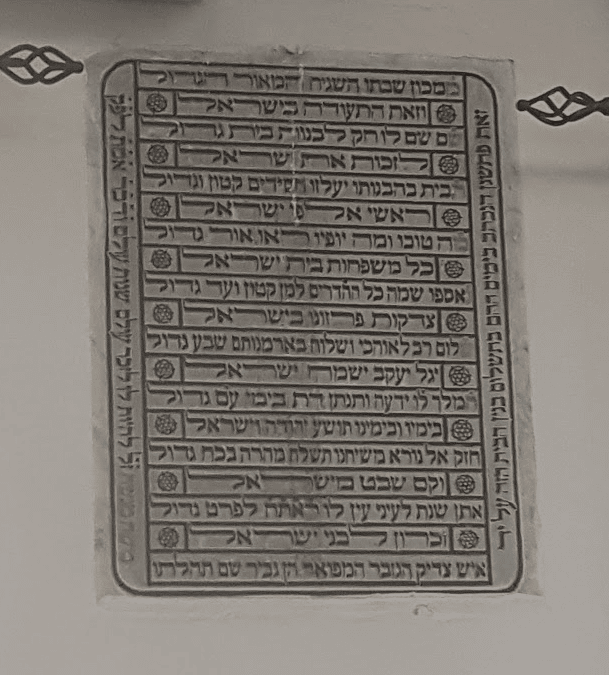

There were plaques in Hebrew embedded deep into the walls, some with cracks and others very smooth.

This is Adam trying to read one. He could tell it was scripture but couldn’t figure it out.

Here is a close up:

Being inside made me feel a little dizzy, and painfully young. It’s a building of stones and pebbles in the floor, a bimah and worn walls and wood banisters and paintings on the wall. The hands that built them and used them are all gone, first by passage of a few hundred years, and then all at once by monstrous genocide.

There were several small rooms off each side of the synagogue, and a courtyard beyond the Bimah. I was in one room when I overheard someone speaking Spanish, specifically with an accent I could understand very well.

It was the older gentleman who had said “No flash, please!” He was speaking to two visitors in very rapid Spanish. Then he switched to Hebrew and greeted two visitors from Israel. When he was done, I introduced myself. His name is Samy Modiano. I asked him if I could ask him questions in Spanish.

“Sure! I speak Spanish, Greek, Hebrew, and Italian. No English, well, a little.”

“No flash please?”

“Exactly.”

He invited me to sit down, and the woman who had greeted us came over to sit next to me. She apologized that she didn’t speak much English, but she did speak Spanish, Greek, and Hebrew, so she would answer any questions I had.

“Ask me anything.”

I asked if this was his synagogue, and he replied, yes. Since he was small, he’d attended this synagogue. He was born in Rhodes. He was born in Rhodes when it was Italian. His mother and father were born in parts of Rhodes that were either Italian or Turkish, which he said with a gesture was a rather large divide.

“From when I was small, I attended here. My father and mother, my entire family.”

“Did you have your bar mitzvah here?”

“No. I was preparing, preparing, studying, studying, all the time, but the Nazis came. I did not have my bar mitzvah.”

He then said something in Greek to the lady beside me, who went to fetch a book from the gift shop.

“This is my book. It’s in Italian, so you can’t read it, though you’re good with Spanish you might make some of it work.”

He turned to the pictures in the middle. “This is my mother. She was born in the Turkish side. This is my father, when he was young. “

Then he turned the page.

“This is my father, a handsome man. My mother. My sister. All dead. Killed by the Nazis. They came, and took us, separated us, and my sister and mother died in Berkinau. I was in Auschwitz.”

Then I noticed his arm. He had a number tattooed on his left forearm.

I have never met in person a Holocaust survivor. I’ve seen videos, and read plenty.

But I’ve never met a survivor in person. Today, there are so few left.

He turned the page. “My beautiful sister. We had so few pictures.”

Then his phone rang, and he had to leave.

So we started the tour of the museum.

If you’re ever in Rhodes, go. Go to this museum. It’s incredible.

The museum starts in the courtyard, then each small stone room holds different artifacts from the Jewish community of Rhodes: religious items and pictures are in different wood cases.

There is one account from one of the few survivors from Rhodes. When they were deported, the Nazis demanded all Jewish men of Rhodes go to the docks to be counted. Then they were arrested. Two days later, the women and children remaining were told that if they didn’t present themselves, the men would be killed.

The Nazis rang the air raid sirens to send everyone else to the bomb shelters, so no one would see them arresting all the Jewish residents and forcing them onto boats. They sailed, then rode trains, squashed into cattle cars, train cars, trucks, and arrived in Birkenau.

The story of the cruelties faced by this one person are probably accounts you probably have heard before. Brutality, whipping, punishment, starvation, sickness and death. The women in the camps would unwind threads from their blankets, and, using slivers of wood, knit socks to keep warm. They were sharing rations and starving, then made to work cleaning other camps hiking hours there and back in the winter.

Two thousand Jewish people from Rhodes were deported by the Nazis. In the end, less than 150 survived. Today there are less than 50 Jewish people in Rhodes, and the descendants of the community are all over the world. One descendant, Aron Hasson, founded the Rhodes Jewish Museum in 1997, and established the Rhodes Historical Foundation.

Outside the museum entrance are the plates with the full names of every Jewish resident of Rhodes taken by the Nazis.

In English at the top of the first plaque, it says:

Every soul had a name.

As they walked through the gates of hell, they became a number.

As they perished and rose to heaven, they remained a number.

Every name deserves to be remembered.

Of the Modiano family, only Samuel (Samy, above, whom I spoke to) and Lucie, his cousin, survived. The survivors are marked by an asterisk. There are very few asterisks.

This is the courtyard of the synagogue as you enter the museum.

You can see how old the walls are, and how there are different stones in different parts of the construction. That’s 440 years old.

The Jewish Cemetery of Rhodes is outside of town – which is standard – but some of the older burial stones are inside the museum. In Hebrew, this stone reads:

Burial stone of the dear, the honor of our master, Moshi Sidi, departed to the house of his world, and was buried the 22nd of Av, the year 5353 (1593). May his soul be bound in the bond of life.

Pop quiz time! This is the Torah in the museum. Guess how old it is – ballpark century guesses are ok. It’s that old.

Here is a closeup of the text – all handwritten, of course. Got any guesses to the age?

This is a 16th century Sephardi Torah, written, the placard says, with 49 lines per column which is unusual.

This Torah dates back to the 1500s. The answer to How old is this Torah? OLD AF.

This isn’t the oldest one, either. There’s an 800 year old Torah that was dated and traced back to the Jewish community of Rhodes a few years ago. It currently lives in Buenos Aires, but the Rhodes community received permission to borrow it and take it on tour of the US in 2004.

(I really hope there were tour t-shirts because I want one.)

And now, it’s time for beautiful dresses, embroidery, and a truly heartbreaking museum collection. The survivors of the Rhodes Jewish community, and their descendants around the world have sent family mementos and ritual items to the museum, showing not only what ritual items and clothing and textiles they used, but who they were, and who sent them.

Nothing in the museum was exhibited without a name, or several: the person who it belonged to, the person who sent it, where they are now. Every item belonged to someone.

There were no tags that just said something like, “A seder plate.” Each item was labeled with text like, “This is Flora’s seder plate, which was donated to the museum by her daughter, who lives in…” etc.

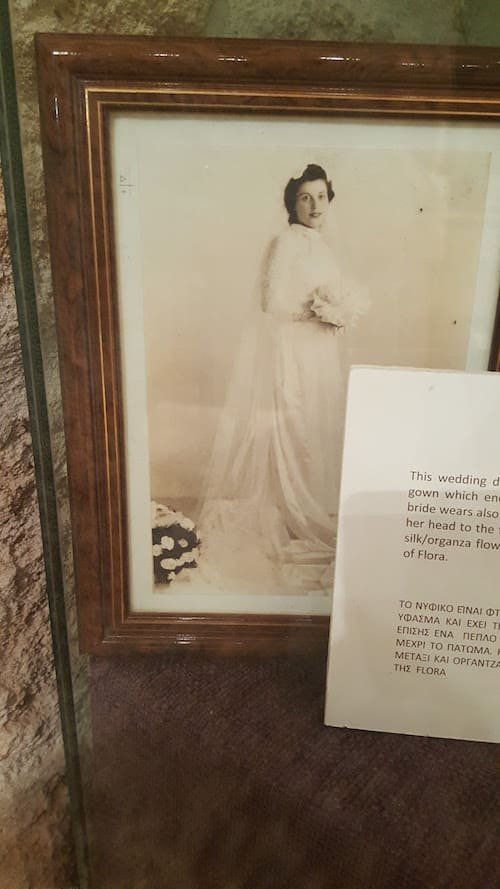

Speaking of Flora: her wedding dress! According to the card at the bottom his wedding dress was worn by Flora, whose daughter Rachel Danon-Franco, sent it to the museum.

I apologize for the reflections in the picture. There were a lot of lights in the room, and, as you know, no flash!

This is Flora:

Silly me forgot to take pictures of all the placards, so I will try to recall what they said. They were donated by the family of Bellina Hassan Gold.

This is a traditional gown in a Turkish style. Obviously for formal wear.

This dress is made from taffeta, and has beautiful ruffled trim and darker red trim on the sleeves.

And this one was labeled, “The Red Dress”

IT SURE IS. This was worn in the 20s (obviously) and according to the placard, it was a dress for a ball attended by Flora’s sister. All of these garments were in remarkably good condition.

Once we left the room of, “Hey, Sarah, you’re going to love this part” (It’s true, I did), we turned a corner and … hello, they had their own mikveh.

A 1500s mikveh!

A mikveh is a ritual bath that is used by women before marriage or after menstruation, depending on their observance. I went into a mikveh when I converted (there are two in north Jersey, in the Caldwells and in the Oranges, so I was dipped in the Oranges). I was very nervous because I dislike being cold, but it was warm and one of my favorite memories of that day.

Looking at a 500 year old mikveh was a somewhat staggering experience. Women had passed where I was standing to immerse themselves there. For hundreds of years.

So while this story is largely sad, here is the hopeful and wonderful part I mentioned at the start which made me tear up.

This was The Grand Mufti of Rhodes, Seyh Suleyman Kaslioglu

In September 1943, according to this story, the Germans took control of Rhodes. Bombings by the British destroyed a large part of the Jewish quarter, and killed 34 Jewish people accidentally. With the German control and the bombings, the Jewish community leaders decided they needed to hide their Torahs.

The Torah is heart of a Jewish community of worship. They contain the first five books of what you might know of as the bible, and they are deeply holy and important objects. They are handmade, they are fragile, and when one cannot be used any longer, they are buried in funerals. Torahs: they are a BFD.

So the Jewish leaders of Rhodes were right: they needed to hide their Torahs.

In secret, the Torahs were given to the Turkish religious leader, the Grand Mufti of Rhodes for safekeeping.

The Grand Mufti was crafty and wise. He hid the Torahs in the Morad Reis mosque.

Where?

IN THE PULPIT.

SERIOUSLY.

According the plaque containing this story and the pictures:

Several years later in 1972, the Grand Mufti confided to a long time Jewish friend, Clement Galante, in a reunion, “One of the greatest moments of my life was when I was able to embrace the Torah, and carry it, and put it in the pulpit of the mosque – because we knew no German would ever think that the Torahs were preserved in the pulpit of the mosque.”

Of the 1676 Jews who were deported, only 151 survived. After the War, the Torahs were returned to the few people of the Jewish community who survived.

Later, in 2004, the historian writing the plaques discovered that not only did the Grand Mufti have a Jewish father-in-law, but that he met regularly with the Jewish leaders of Rhodes, including the Grand Rabbi. Their communities had been close to one another for generations.

One last picture! Thank you for sticking with me.

Before we left, we asked if we could take a picture with Samy, who had told us so much about the synagogue when he was a boy. He was delighted. Over here! This is the best spot! Sit here! Move close!

Please meet Samy Modiano, survivor and multi-lingual guide to Kahal Shalom in Rhodes. (I’m on the right, in the sunglasses, and Adam is on the left). He and his cousin were the only members of his family to survive the Nazi deportation and genocide.

Of over 1600 people deported from Rhodes, he is one of the 151 who lived, one of the a handful left in the Jewish community of Rhodes. “I’m here every summer,” he said. “Here in the synagogue.”

There are so few survivors left who can talk about their lives, what happened to them and to their families. There are so many communities like Rhodes where a handful of people are left to tell the story of what had been thousands. The pictures we saw in the museum were pictures of a thriving community. For one wedding in the late 30s, there were hundreds upon hundreds of people in the very narrow streets we’d just walked down, the bride and groom two spots in a sea of people escorting them.

As you know, I converted to Judaism. And in the years since, I’ve worked for and worked with literally dozens of different Jewish charities. I worked for organizations that try to present a unified voice on dozens of issues, and I worked for organizations that devote themselves to one specific problem or issue.

There is always a historical foundation of something. Or fifty. Or a hundred. I’ve lost count. So much history, specifically history that is lost. And I sort of thought I understood why there were so many.

Ha. No. I get it now. I understand. And I’m sorry I ever questioned why they exist.

They exist because the kiddush cup, the tallit clips, the seder plate, and etrog holder used by someone’s great aunt, someone’s father in law, someone’s grandmother, are in a museum now, with their names on them, explaining what they are, what they’re used for, and whose fingerprints are probably still inside.

History isn’t only what happened, or what group it happened to. History is also the personal relics and memories contained in a ritual item, a common observance, or a shared way of looking at the world. History is in the individuals.

Everything about Kahal Shalom and the Jewish Museum of Rhodes focuses on the people who lived there, the tangible objects that house their history, and the remnants of their memories:

We were here. Now, we’re not. But we’re still here.

So part of “never forget” is making sure I don’t forget what I’ve learned. Thanks for indulging me.

Links for more information:

The Rhodes Jewish Museum

Kahal Shalom Synagogue, Rhodes, Greece

There are several videos of Sami Modiano talking about his life and his experiences, most in Italian. His book, Per Questo Ho Vissuto (La mia vita ad Auschwitz-Birkenau e altri esili) (That’s Why I Lived: My Life in Auschwitz-Birkenau and Other Exiles) was published in 2013 and is available on Amazon.it. He will be 87 years old on Tuesday, July 18. (Feliz cumpleanos!)

by SB Sarah · Jul 14, 2017

Source Smart Bitches Trashy Books

eSefarad Noticias del Mundo Sefaradi

eSefarad Noticias del Mundo Sefaradi