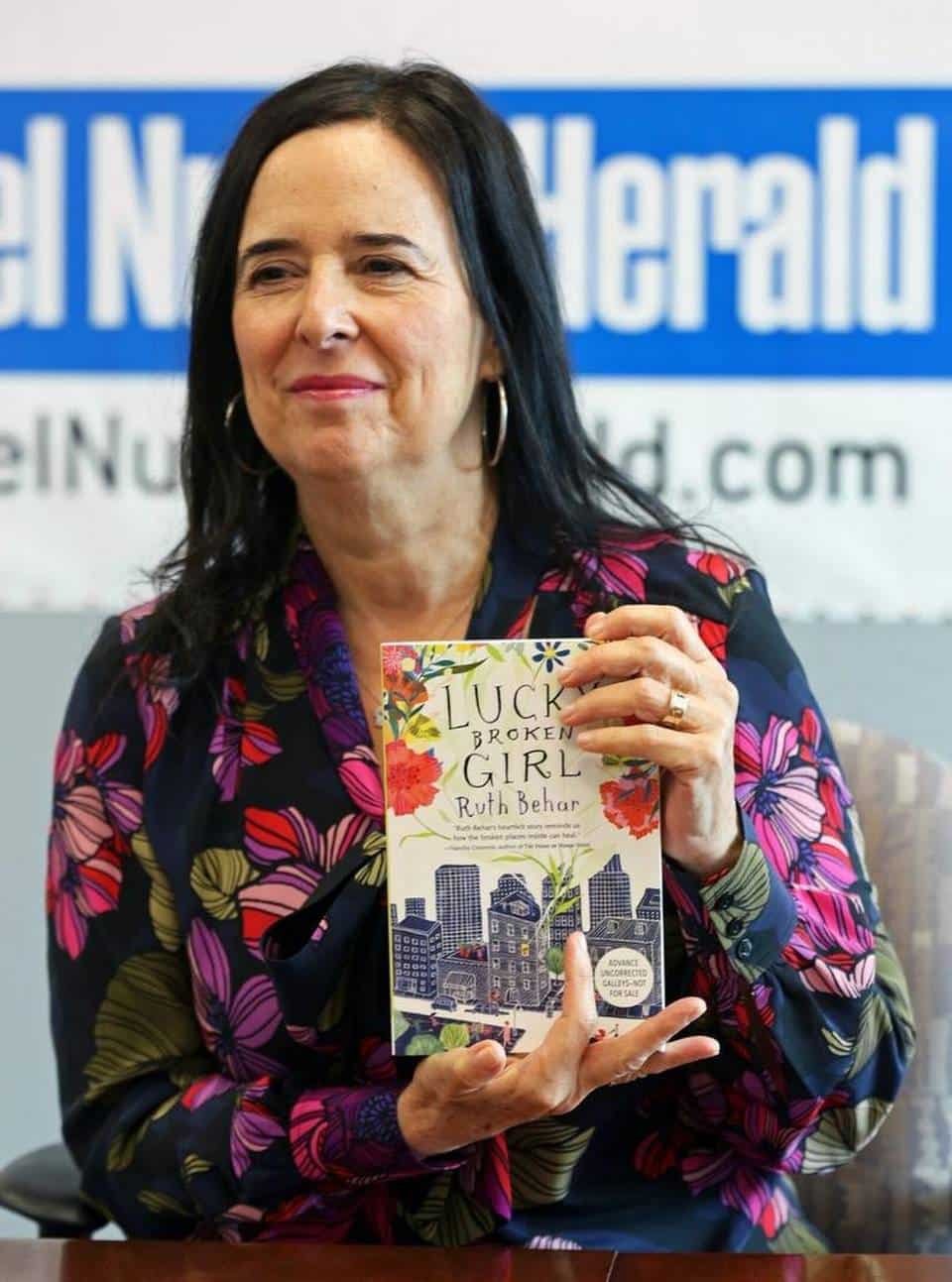

A Jewish Cuban girl who flees Fidel Castro’s regime and lands in multicultural New York City is the main character of the first novel by anthropologist Ruth Behar, designed to teach U.S. children about belonging, identity and immigration. C.M. Guerrero Miami Herald

Jewish Cuban girl who flees Fidel Castro’s regime and lands in multicultural New York City is the main character of the first novel by anthropologist Ruth Behar, designed to teach U.S. children about belonging, identity and immigration.

Behar, born in Havana to a Jewish Cuban family and a professor at the University of Michigan, has been traveling for decades to Cuba, where she has been deeply involved in efforts to assist the Jewish community.

Her novel, Lucky Broken Girl (Penguin), reflects her own experiences assimilating into U.S. culture as well as her anthropologist’s eye for cultural diversity she found in New York City when her family arrived in 1959, she told el Nuevo Herald.

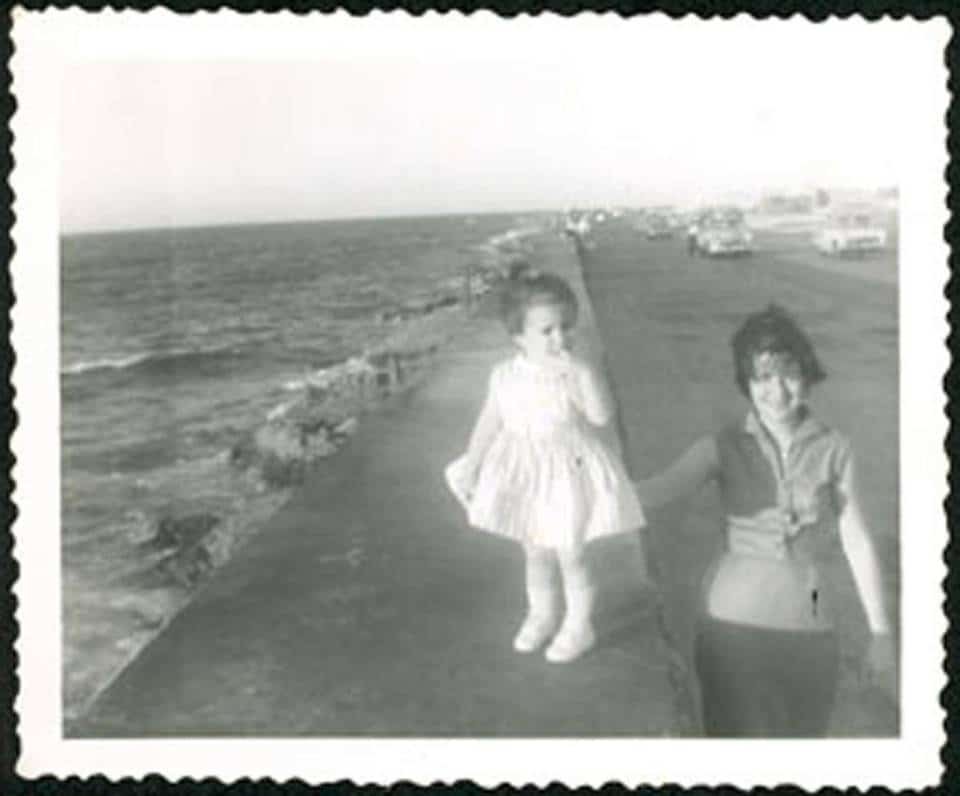

Behar suffered a terrible car accident at the age of nine and had to spend the next year in bed, an experience shared with her protagonist, Ruthie.

“It’s my first novel for young readers,” she said. “There’s not a lot of literature about a girl who is Cuban and Jewish and lives in New York, who had the experience of being in a body cast … There are many idiosyncratic factors that come together in this book.

“If there’s a message in the novel that’s very important for children,” she added, it’s that “maybe there’s a change in your life and you’re not the person you were before, but that’s not a bad thing. You have to accept it.”

MAYBE THERE’S A CHANGE IN YOUR LIFE AND YOU’RE NOT THE PERSON YOU WERE BEFORE, BUT THAT’S NOT A BAD THING. YOU HAVE TO ACCEPT IT.

Ruth Behar, author

The novel, which will go on sale in April, comes with a teaching guide for sixth grade students that is focused on the immigrant experience, the historical context of Cuba and New York City in the 1960s, the complexities of cultural identity and the healing powers of art and culture.

Behar is part of the generation of Cuban children who emigrated to the United States after 1959, when Fidel Castro seized power, and then as adults tried to reconnect with the island, in many cases against the wishes of their parents because the Castro government was still in place.

The parents “suffered a lot because they had nothing against Cuba and they did not want to leave,” she said. “That made us very curious about recovering this island that our parents had lost, and seeing where we belonged.”

After her first return to Cuba as a student in 1979, during a brief opening by the Carter administration, Behar started to visit the island regularly in the 90s. Long before cultural exchanges became popular, she edited the book Puentes a Cuba/Bridges to Cuba, a collection of writings by Cuban and Cuban American authors.

“At that time, no one was doing that kind of project, bringing together the voices of Cubans here and there. It was a bit crazy, before the internet. You went, met people and sometimes they gave you their only copy of their manuscript,” she recalled.

“There was a lot of interest in publishing in the United States, and I was the bridge,” said Behar, adding that her work was to establish connections with Cubans and their culture and not the government, as some critics alleged.

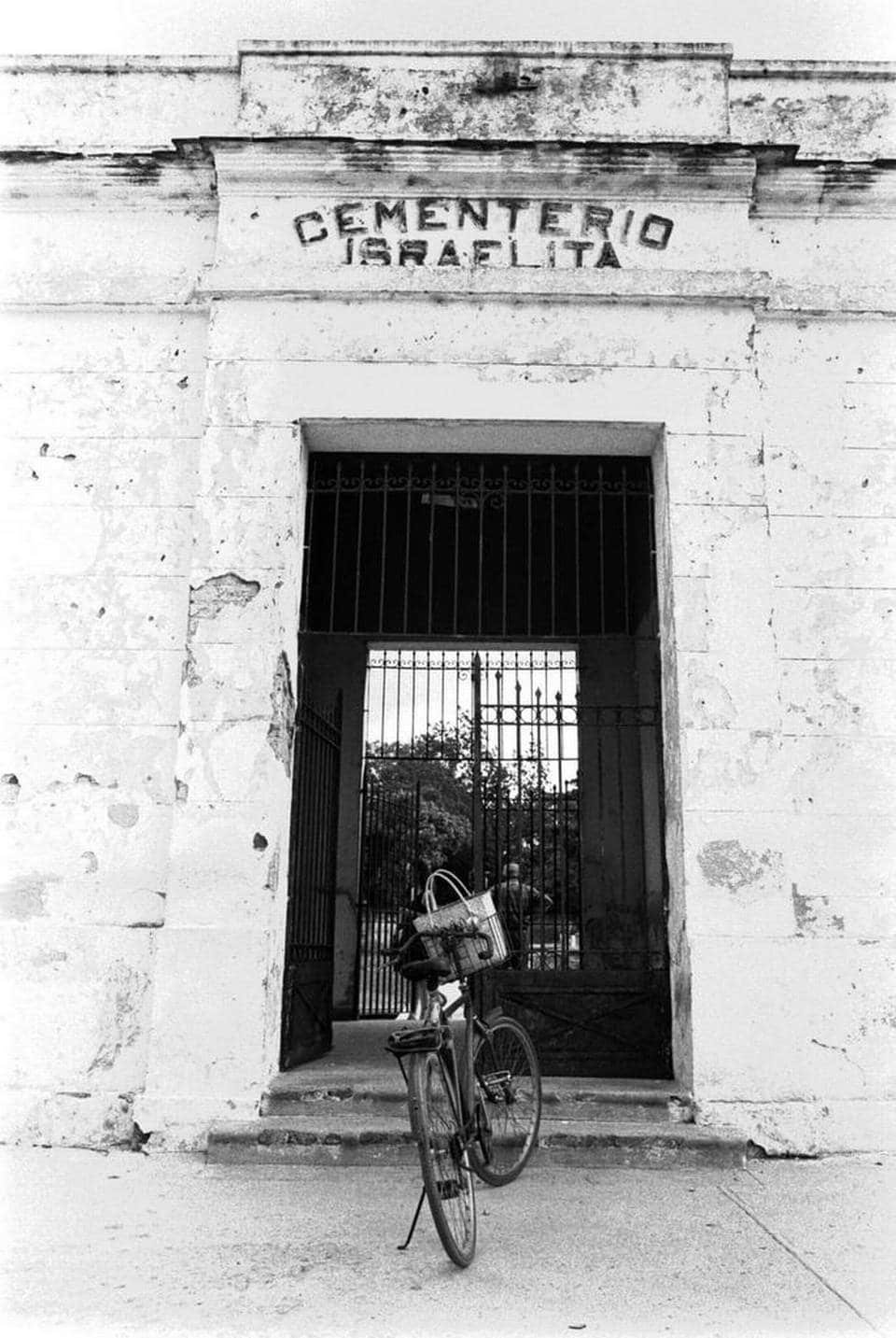

During her trips to Cuba, Behar also became deeply involved with the island’s Jewish community, estimated at 15,000 at its pre-Castro peak. She puts its current size at about 1,000 people.

Starting in the 90s, and thanks in part to assistance from the United States, community members learned more about their religion and culture and revived services in the synagogues. Behar produced a documentary, Adio, Kerida, in the early 2000s, about her Sephardic and Cuban roots. Her book, An Island Called Home: Returning to Jewish Cuba,has become a virtual guidebook for U.S. Jewish groups visiting the island.

“The Jewish community in Cuba today is small but well prepared. They don’t have a resident rabbi but they know the prayers, the rites of Shabbat, celebrations like Hanukkah,” said Behar, who added that the U.S. Jewish community is “tremendously interested” in helping its island counterpart.

THE JEWISH COMMUNITY IN CUBA TODAY IS SMALL BUT WELL PREPARED.

Ruth Behar, author

Behar was in Havana for the recent opening of the opera Hatuey, a project she assisted by connecting U.S. composers Frank London and Elise Thoron with Cuba’s Opera de la Calle company. The opera is based on a 1931 poem in Yiddish by a Ukrainian Jew who fled to Cuba to escape the programs.

Behar also arranged for a concert at the Beth Shalom synagogue in Havana, with songs in Hebrew, Yiddish and Ladino.

The author and academic, who in 1988 became the first Hispanic woman to win a MacArthur Fellowship, also created and for three years directed a University of Michigan program for U.S. students to spend three months in Cuba.

What can a U.S. university student learn in Cuba?

“There are many issues to study in Cuba, first of all the transition from socialism to capitalism…at least at the economic level,” said Behar. “And for those interested in art, Cuba is very rich in visual arts, dance, music and of course the Afro Cuban culture.”

The students get “a perspective on a society that is so near but is so different from the United States,” she said, and learn “how Cuba has lived with the embargo, and with this very tense relationship.”

Most interesting to the students, she added, are the “contradictions, for example if people are free or not free,” and the signs of former wealth, evident in Havana’s architecture, in a country that today is “underdeveloped.”

In her influential and controversial book, The Vulnerable Observer, published 20 years ago, Behar questioned the objectivity of anthropology and “cold observation…that kind of anthropologist who must keep a distance from culture.” That’s also a very masculine approach to the research, she argued.

Behar acknowledges that people who are studied by anthropologists sometimes share intimate details that make them vulnerable and have an emotional impact on the researchers.

Her advise to students of anthropology is simple: “Do nothing that can harm the people who have given you their stories. If you believe it can harm them, don’t write it.”

eSefarad Noticias del Mundo Sefaradi

eSefarad Noticias del Mundo Sefaradi