Helen, Sautee and the Nacoochee Valley: Part Three

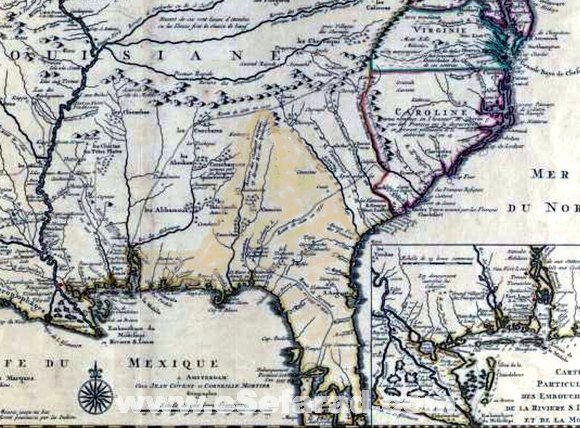

In 1824 traders passing through the Cherokee Nation that had been relocated to the northern tip of Georgia, reported finding gold. Because the true history of that era has been distorted by myths it is not clear how the gold was re-discovered. Almost all the maps of the 17th and early 18th centuries described (what is now) northern Georgia, as a gold-bearing region. Perhaps someone found an old map and sneaked onto the Cherokee lands, found gold nuggets in its streams, and quickly raced back to the state capitol in Milledgeville, GA.

One of the prevailing myths one sees in history books and web sites is that the Cherokees were evicted from Georgia because gold was discovered on their lands. This is not true. They had been evicted from the gold fields for 16 years prior to the Trail of Tears. The first response of Georgia’s government was to inform the few Cherokees living on gold-bearing soils that their chiefs had misunderstood the Treaty of 1794.

Thoroughly crushed by a series of catastrophic defeats in the 1700s, the now-docile Cherokees left the region with little protest. The United States’ first major gold rush soon began. The miners had some contact with the departing Cherokees; enough to learn the Native geographical place names. They assumed the words were Cherokee. Most of these words were actually Creek, but the miners assumed that the Cherokees had always lived in the Nacoochee Valley. Thus began a series of myths that became historical facts in the 20th century.

Wealthy Georgia and South Carolina planters quickly bought up major sections of the mountain streams. South Carolina Senator John C. Calhoun acquired a large section of Dukes Creek in the Nacoochee Valley. He made a fortune off that investment.

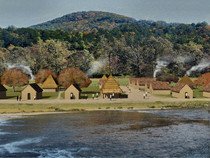

Almost immediately after starting the diggings, Calhoun’s employees found the ruins of a village . . . a settlement of at least 20 European style houses, some utilitarian structures and a pit lined with logs. They also found many mining tools that appeared to be from the 1600s or late 1500s. Among the many domestic artifacts found was a cigar mold.

The discovery of a Spanish settlement in the Georgia Mountains was almost forgotten until 1873 when Charles C. Jones, Jr. published his landmark book, Antiquities of the Southern Indians, Particularly of the Georgia Tribes. The book received international acclaim and is still considered to be a very useful classic of archaeological literature. Jones correctly interpreted artifacts to state that the Creeks had built all the mounds in the Nacoochee Valley; the Spanish had occupied the valley for at least a century; and that the Cherokees had lived in the Georgia Mountains for a relatively brief time period. That part of his book was conveniently forgotten until the very late 20th century.

Portuguese Conversos flee to the New World

The evidence of a European occupation of the Southern Highlands prior to the arrival of the Cherokees is substantial, but has NEVER been researched by professional archaeologists. No professional effort has been make to locate the Dukes Creek Spanish village site.

Almost all the evidence suggests that the Spanish colonists in the Southern Highlands were Jewish. Some vague North Carolina cultural memories recall “Portuguese” miners living in the mountains. These were, in fact, were Sephardic Jews who escaped Iberia via Portugal. They told strangers that they were Portuguese so as to conceal their Jewish heritage. In 1492 King Fernando and Queen Isabela issued an edict expelling all Jews and Moslems from their kingdoms. Jews, who refused to become Catholics were expelled from Portugal in 1597. Jewish refugees fled in all directions, but many ended up in the Portuguese colony of Brazil.

After Spain absorbed Portugal in the 1540s, Jews who pretended to be Catholics were able to move around the Spanish Empire in order to conceal their heritage. The vibrant city of Cartagena, Columbia attracted a community of Conversos, as converted Jews were labeled. These well-educated citizens became particularly active in mining and international trade.

In 1610, the Spanish crown issued a decree that established the Inquisition in Cartagena. Its jurisdiction was all of the Caribbean Islands. Wealthy Conversos were targeted. The Crown wanted their estates. All those who were immediately arrested were Portuguese Jews. Many Conversos left the region. Thus, the date, 1615, of a Ladino (Sephardic Spanish dialect) stone inscription in the Smoky Mountains matches perfectly with what else was going on in the Spanish Empire. (See http://www.examiner.com/architecture-design-in-national/north-carolina-rock-s-inscription-will-ultimately-change-history.)

Spain claimed all of the Chattahoochee River Basin up the river’s source, north of Helen, GA, until 1745; after losing the War of Jenkins Ear. Spanish maps accurately portrayed the location and the length of this river, while the cartography of most other Southeastern rivers was grossly inaccurate. The Spanish obviously had traveled up the river to its source, even though there is today no known records of such expeditions. Spanish mining claim marks have been found on rocks along Nickajack Creek in Smyrna, GA (Cobb County-Metro Atlanta.) The location is about five miles from the Chattahoochee River.

In the early 1690s, a joint Cherokee-English patrol climbed a mountain top and observed the smoke of many fires in the Nacoochee Valley. The Cherokees told the English officers that the smoke was from the smelting furnaces of the many Spanish gold miners who lived in the Nacoochee Valley. Presumably, the Spanish Converso community was either killed or driven out by the Cherokees during the Queen Anne’s War, which lasted from 1702 to 1714.

In 1745 Cherokees entered the section of the Tuckasegee River Valley around modern-day Silva, NC. They reported to English authorities in Charleston that there were no Native Americans in the region, but there were several villages occupied by strange white men, who were silver smiths. They spoke a language similar to Spanish (Ladino?) . . . had skin the color of Indians and long beards. The Cherokees said that they lived in cabins with arched windows and “worshipped” a book (the Torah?) The Cherokees stated that they drove these people out of the region.

In 1781 Colonel John Tipton and Colonel John Sevier led a party of 80 families from Shenandoah County, VA to settle eastern Tennessee. They later stated that the wagon train passed through several villages in SW Virginia and NE Tennessee, which were occupied by Spanish-speaking Jews. Most of these Jews earned a living as gold and silver smiths.

Sequoyah

One of the many mysteries about Sequoyah is his skills as a silver smith. From age 10 to 15 he lived with his mother on the Little Tennessee River. He then joined the Chickamauga Cherokee guerillas, with whom he fought continuously until 1793, when most of their army was killed at the Battle of Etowah Cliffs in what is now Downtown Rome, GA. Sequoyah took refuge in the Natchez-Cherokee village of Pine Log. He immediately started making a handsome living as a skilled silver smith. In his spare time, he developed his famous syllabary.

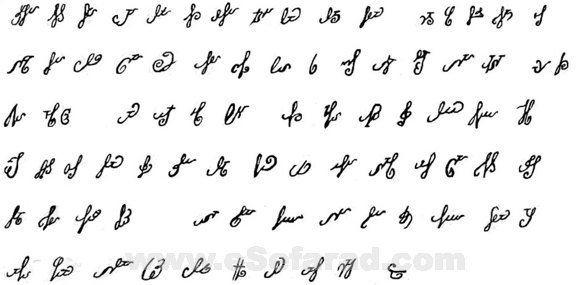

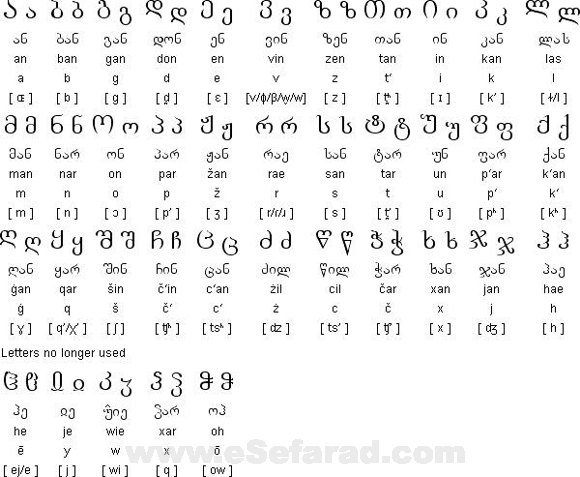

The syllabary that Sequoyah created, incorporated letters identical to those in Medieval Georgian script, which was based on the Jewish Aramaic script. (See the attached slide.) Elias Boudinot, editor of the Cherokee Phoenix newspaper, changed Sequoyah’s original designs so that they would resemble Roman style lettering. How did Sequoyah learn how to create fine silverware? How could he have possibly known Medieval Aramaic and Georgian script? The possible answer points toward his father actually being a Sephardic silver smith. The word Sequoyah was originally his mother’s name and has no meaning in Cherokee, but in its Creek language form meant “war captive” in the 1700s.

There is currently no knowledge of exactly what happened to the Conversos of the Southern Highlands. There is a hybrid population in the mountains of Virginia, Tennessee and Kentucky who call themselves the Melungeons. Many have been found to carry Mediterranean DNA along with the DNA of Northern Europeans and Native Americans. However, it is not likely that the Sephardic gold miners of the Nacoochee Valley traveled northward through Cherokee Territory to escape the Cherokees. Those that survived Cherokee attacks may have moved to French Louisiana, which had no Inquisition.

by Richard Thornton

Architecture & Design Examiner

Richard Thornton is an architect and city planner, with a very broad range of professional experiences. His practice is concentrated in the Southern Highlands of the United States, but also has included projects in other parts of the nation and in Sweden. He has been the architect for a broad range of institutional, commercial and residential projects. Richard is particular noted for his work in downtown revitalization, historic preservation and architectural history. and won several historic preservation and urban design awards. He was the first recipent of the Barrett Fellowship, which enabled him to spend several months in Mesoamerica studing its pre-European civilizations under the auspices of the Museo Nacional de Antropologia in Mexico City. In 2004 he was approached by some members of the Muscogee (Creek) National Council about carrying out research into Native American architectural history and writing books for Native American students from these studies.…

Richard Thornton is an architect and city planner, with a very broad range of professional experiences. His practice is concentrated in the Southern Highlands of the United States, but also has included projects in other parts of the nation and in Sweden. He has been the architect for a broad range of institutional, commercial and residential projects. Richard is particular noted for his work in downtown revitalization, historic preservation and architectural history. and won several historic preservation and urban design awards. He was the first recipent of the Barrett Fellowship, which enabled him to spend several months in Mesoamerica studing its pre-European civilizations under the auspices of the Museo Nacional de Antropologia in Mexico City. In 2004 he was approached by some members of the Muscogee (Creek) National Council about carrying out research into Native American architectural history and writing books for Native American students from these studies.…

Source: Examiner

eSefarad Noticias del Mundo Sefaradi

eSefarad Noticias del Mundo Sefaradi