In Seattle’s large Sephardic community, offers of Spanish and Portuguese citizenship are met with more skepticism than forgiveness

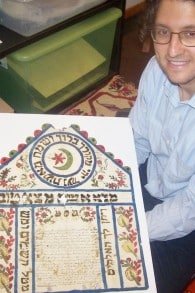

University of Washington Prof. Devin Naar is spearheading the Sephardic Studies Digital Library and Museum, a first-of-its-kind project featuring 500 historical books and thousands of rare historical documents, many from Seattle families. (Janis Siegel/The Times of Israel)

SEATTLE — University of Washington Prof. Devin Naar is quickly becoming a de facto custodian of the historic remnants of the Northwest’s Sephardic Jewry’s day-to-day lives.

During an interview in his modest Seattle campus office, overlooking well-groomed walking paths lined with lush shady trees, Naar said he has only to look back a couple of generations within his own family to recall his ancestors’ persecution and pain in the Mediterranean countries they fled over a hundred years ago.

“My family came from Spain in 1492 to Portugal, and in Portugal they appeared to have been forcibly baptized in 1496,” said Naar. “They wound up fleeing the Inquisition in the 1530s from Portugal and settling in Salonica, which was then in the Ottoman Empire. They remained there until the 20th century when my grandfather came [to the US] in the 1920s.”

But with recently passed new laws in Spain and Portugal, which seek to grant citizenship to descendants of their persecuted and expelled Jewish communities, Naar and thousands of Sephardic Jews in America ponder the meaning of the new legislation, and whether they’ll take the countries up on their offers.

The young professor is an encyclopedic source of information on Sephardic Jewry. Naar, who was born and raised in New Jersey, is currently the Marsha and Jay Glazer endowed chair in Jewish Studies and chair of the Sephardic Studies program at the University of Washington. He is spearheading the Sephardic Studies Digital Library and Museum, a first-of-its-kind project featuring 500 historical books and thousands of rare historical documents, many from Seattle families.

Lining his office: a Sephardic ketubah, a revered rabbi’s portrait, and a one-of-a-kind 1916 Guidebook for Sephardic Immigrants. The guidebook was used to tutor the eager Sephardic newcomers in the ways of America, passing on rules of etiquette for guests and teaching them, phrases like, “Please sit down and have a piece of cake.” The manual, published in New York in 1916, was written in three languages, Ladino, Yiddish and English.

The Sephardic scholar wouldn’t say if anyone in his family was planning to apply to Spain or Portugal for citizenship now that the legislation finally passed in Spain.

However, he said that today’s offer of citizenship from Spain echoes similar overtures made over a century ago.

At that time, he said, hundreds of Sephardic Jewish businessman and their families living in the diaspora accepted the offer.

“In 1898, when Spain loses its American colonies – Guam, the Philippines, it is devastated by this loss, for economic reasons as well as prestige in Europe,” Naar said. “They are looking for other kinds of economic opportunities.”

Again, in the early part of the 20th century, Spain offered its far-flung former citizens another chance to come home.

“In the 1920s, there was an opportunity for Sephardic Jews to claim Spanish citizenship,” said Naar, “and then Spain made a formal decree in 1924.”

Spain’s current law opened a three-year window within which Jews need to apply with a possible extension of one year. Spain also wants would-be citizens to pass a modern Spanish language test.

Portugal has no time restrictions for filing in the law, however it requires applicants to prove ancestral residency in the country prior to 1492.

Both laws require applicants to obtain several documents that must be notarized by the proper authorities, religious and non-religious. Some believe all of it will be too much for many Jews to accomplish.

For Rabbi Marc Angel, a Seattle-born Orthodox rabbi and the rabbi emeritus of Congregation Shearith Israel, a historic Spanish and Portuguese synagogue in New York City, it’s simply too little, 500 years too late. The difficult application process only compounds the original insult.

In a blog posted on the Institute for Jewish Ideas and Ideals, a site he founded where he is currently the director, Angel lays out his reaction to the offers and is unequivocally and unapologetically cynical.

Angel told The Times of Israel in an email that his views have not changed.

“I have zero interest in a Spanish passport, and feel this enterprise is more in the category of a public relations stunt than a genuine effort to ‘atone’ for 1492,” wrote Angel.

“I don’t have a sense of a massive interest among Sephardim in obtaining Spanish passports. I have had a few requests to write a letter of recommendation. I’ve also heard from people is South America who seem interested. But from what I read, Spain is one of the most anti-Semitic countries in Europe. Real atonement entails cleaning the Spanish culture of anti-Semitism,” said Angel.

In his blog post he puts it even more bluntly: “Spanish Jews were terrorized, murdered and forcibly baptized. This was not merely hatred of Judaism, but a hatred of those of Jewish blood… Many Sephardim — including me — have so much of Spain within us. A few kind words and a modest number of Spanish passports cannot erase centuries of hatred and injustice.”

Today, both Spain and Portugal continue to feel the effects of deep recessions that rocked their economies nearly three years ago.

Naar doesn’t deny that there may well be an economic motive in the latest citizenship laws, but, he said, it really depends on who you ask.

“I don’t know, it’s a huge debate,” said Naar. “Some people think that this is a moment of reconciliation and justice, and some people say, ‘You only want us now because your economy is bad and then you give us extra terms in order to get this citizenship?’”

Rabbi Ron-Ami Meyers from Congregation Ezra Besseroth, a historic Seattle Sephardic synagogue founded by immigrants from Rhodes told The Times of Israel that the Jewish community has not had time to “digest things and to weigh in on both the idea and the practicality of the concept.”

“On a day-to-day basis, I have had a few conversations,” said Meyers. “I think that the whole story is in its early stages, even though the Spanish government has been sitting on this for a long time.”

However, Doreen Alhadeff a 64-year-old Jewish Sephardic Seattleite and mother of two adult sons said she will be applying for Spanish citizenship soon.

Alhadeff’s family arrived in the US from Turkey in 1902 and settled in Seattle in 1906, where her grandmother, Dora Levy helped settle other Sephardic families.

“I’m going to move forward with it and I think the cynicism is unwarranted,” said Alhadeff, who is fluent in Spanish. “I think the language requirement is going to be very difficult and prohibitive for most but a lot of people are looking at this with a closed mind. This is the land of our ancestors.”

Alhadeff is one of four co-founders of the newly formed Seattle Sephardic Network; a group that hopes to represent the nearly 4,000 Sephardic Jews in Seattle who largely came from Turkish and Rhodesli families. Interestingly, Seattle is the third-largest Sephardic Jewish population in the US. The network supports the new laws and plans to hold an informational community briefing in the near future.

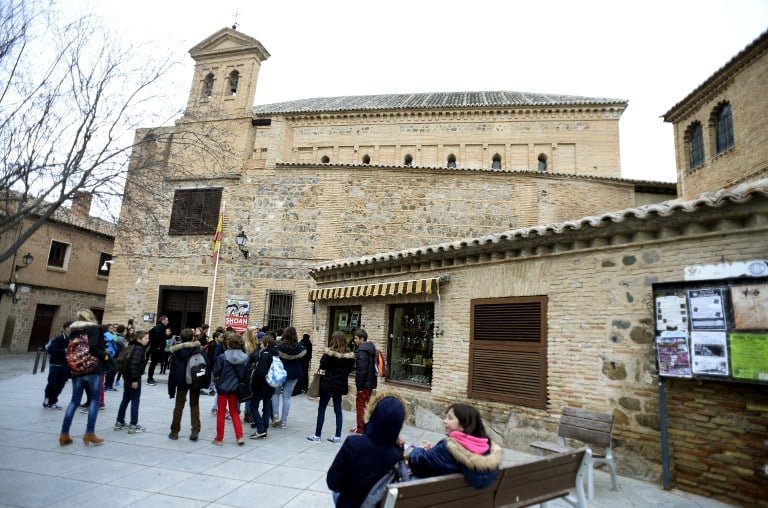

Children stand near the «El Transito» synagogue and Sephardic Museum in Toledo on February 27, 2014. Founded in 1357 by Samuel Halevi Abulafia, advisor and treasurer to King Pedro of Castile (also known as Pedro the Cruel), the synagogue was converted into a church following the expulsion of the Jews from Spain in 1492. Two dozen cities and towns across Spain have banded together in a Network of Jewish Quarters to try to revive and promote their Jewish history by building monuments, putting up signs identifying historic sites and hosting concerts, lectures and other cultural activities.AFP PHOTO / GERARD JULIEN

During a recent trip to Spain, Alhadeff was impressed by the money it’s spending in resurrecting local monuments and Jewish landmarks into a kind of a 24-city interpretive exhibit seeking to restore part of its Jewish past.

Alhadeff sees it as an opportunity to reconcile her family’s past and restore a legacy for their future. She rejects the notion that Spain’s offer is merely a revenue-boosting economic ploy to attract money into its coffers – nor does she view it as an attempt by Spain to minimize its brutal history against the Jewish people.

“They know it was the wrong thing,” said Alhadeff, “but they’re trying to correct a historical wrong. It’s a different place then it was. It’s like a renaissance for the Sephardic people right now.”

July 18, 2015

Source: Time of Israel

eSefarad Noticias del Mundo Sefaradi

eSefarad Noticias del Mundo Sefaradi