Versión en Español aqui.

As you walk through the city centre of Thessaloniki, at first you are likely to hear nothing but the roar of the scooters zooming down the streets of Greece’s second-largest city.

Usually, the more senior locals escape the city traffic in cafés, eating the traditional sesame-covered doughnut, kouloroi, and telling each other anecdotes in Greek.

But if you are lucky enough to meet Jacky Benmayor, you can hear another story, told in a completely different language: Ladino.

Jacky Benmayor is the last speaker in Greece of Judeo-Spanish, or Ladino, a language derived from Old Spanish spoken by the Jews driven out of Catholic Spain in 1492.

As the guardian of a language close to extinction, Benmayor’s aim is to revive the sound of his mother tongue. Two years ago, after retiring, Benmayor, now 75 years old, started teaching Ladino courses at the University of Thessaloniki.

Ladino sounds like an exotic language to most of Benmayor’s students, yet just over a hundred years ago it was the most spoken language in Thessaloniki. “Many people still consider Jews to be extraneous to the city, when in fact they are its oldest residents,” Benmayor tells Euronews.

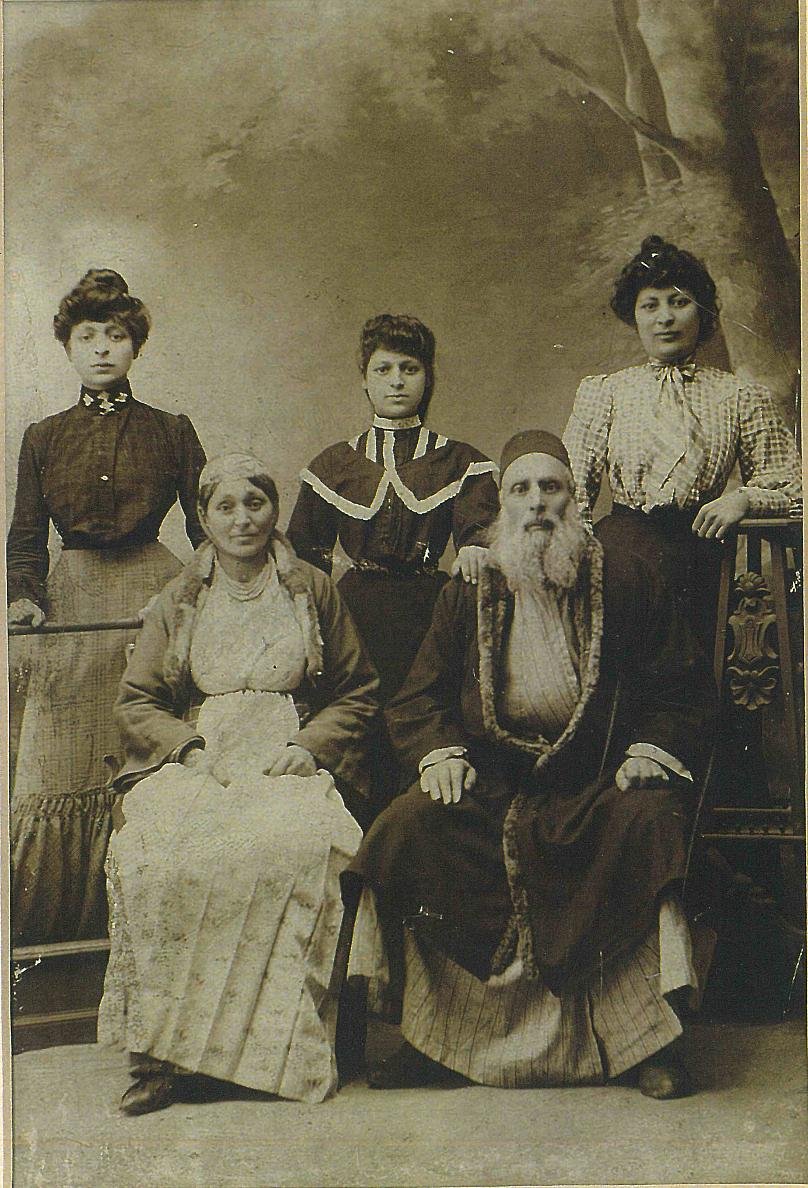

At the beginning of the 20th century, the Jewish community of Thessaloniki, known as ‘the mother of Israel’, was the largest, and the first language that resounded in the city’s streets was not Greek but Ladino, handed down over the centuries by Jewish families who had taken refuge in the town and who coexisted with the Greek and Turkish communities.

«In 1492 Jews in Spain either converted or were expelled. Many of them found refuge in Thessaloniki, which at the time was ruled by the Ottoman Empire and was depopulated,” Evangelos Hekimoglu, curator of the Jewish Museum of Thessaloniki, tells Euronews.

“The core of vocabulary and morphology of Ladino is Spanish, but over the years, the Jewish refugees have enriched it with Greek, Turkish and Hebrew words, so that scholars still question whether Ladino should be considered a dialect of Spanish or a language in its own right,” Hekimoglu explains.

Moreover, although Ladino is derived from Spanish, its writing is usually not in Latin characters but in the Hebrew alphabet.

The Jewish community had such an influence on the life of Thessaloniki that most newspapers at the beginning of the 20th century were printed in Ladino, while on Friday afternoons, at the beginning of the holy day for Jews, silence fell over the city.

Then, following the German occupation during the Second World War, the Jewish community almost disappeared: 46,000 Jews were deported and less than 2,000 returned to Thessaloniki. More than 90% of the total Jewish population was annihilated: only the Jews of Poland experienced a higher level of destruction.

After the Holocaust, Jewish families struggled to pass on Ladino, even for political reasons. “Many survivors didn’t want to speak the language that had made them targeted. They believed that if extermination had happened once, it could happen again. As a matter of consequences, Jewish families claimed that they were first and foremost Greeks,» Hekimoglu notes.

Benmayor’s father, Leon, was deported to Auschwitz at the age of 27. “My father was the only member of his family to survive: he was not inclined to speak about his experience in the concentration camp, but he taught me Ladino, which was the first language spoken in my family,” Benmayor says.

During the German occupation, the former Jewish cemetery was destroyed to free up space in the city centre and thousands of gravestones were used as construction material for new buildings. To date, many of these gravestones written in Ladino have been found around the city in unusual places such as storehouses, private villas or even on the seabed of the Gulf of Thessaloniki.

Every time an ancient gravestone is discovered, Benmayor is the community member in charge of translating it. «Around 150,000 gravestones were removed from the cemetery. Many inscriptions reveal important information not just about the death, but also the life of the community members: it’s like reading the newspapers of the time» Benmayor explains.

In the post-war period, the history of the Jewish community, now reduced to a few hundred people, threatened to be forgotten. “The Holocaust was taboo for the society: even the death camps survivors felt the need to hide what have experienced in order to grieve. Only in the 1980s their sons and some historians took a deep dive into the community’s history and started to promote it,” Hekimoglu argues.

A renewed interest in preserving the city’s Jewish cultural heritage is spreading through Thessaloniki. Most of the students who attend Benmayor’s lessons are not Jews, but historians and archeologists interested in reading the city’s historical sources, such as archives and tombstones.

Moreover, a museum and a cultural centre dedicated to the Holocaust is planned to be built on the waterfront of Thessaloniki, while tourism from Israel, before the pandemic, was steadily increasing.

Outside Greece, there are still other communities descended from the Jews driven out of Spain in 1492 who speak Ladino. The largest community of speakers is now in Istanbul. Benmayor communicates with some of its members on a WhatsApp group called ‘Estamos uatsappeando’, which means ‘we are chatting via whats app’.

At the same time, Ladino has been attracting more and more interest in academia: universities in Europe, Israel and the United States have opened courses on the language. “I hope that today scholars will become future ambassadors of Ladino in the world,” says Benmayor.

On his father’s grave, he wanted to inscribe ‘Non ti scordar di me’, the name of an Italian song meaning “don’t forget about me”.

«My father really loved to sing that song” Benmayor recalls. «After all, preserving the memory of our past means remembering our loved ones”.

Elena Kaniadakis

Fuente: euronews.com

eSefarad Noticias del Mundo Sefaradi

eSefarad Noticias del Mundo Sefaradi