By Uzay Bulut

Gatestone Institute

The latest anti-Semitic statement in Turkey was made on November 21 by Dursun Ali Sahin, the governor of Edirne, a city in Eastern Thrace. Governor Sahin announced that because he was angry at Israel, he would turn the city’s synagogue into a museum. “While those bandits [Israeli security forces] blow winds of war inside al-Aqsa and slay Muslims,” he said, “we build their synagogues. I say this with a huge hatred inside me. We clean their graveyards, send their projects to boards. But the synagogue here will be registered only as a museum, and there will be no exhibitions inside it.”

In response to the uproar that followed, Governor Sahin phoned the Chief Rabbi of Turkey, Ishak Haleva, to apologize and, according to the newspaper, Salom, said his statements had been misunderstood and distorted by the media.

The Director General of the General Directorate of Foundations, Adnan Ertem, then said that the synagogue would, after all, remain a house of worship.

More shocking, however, is the demographic makeup of Edirne’s current population.

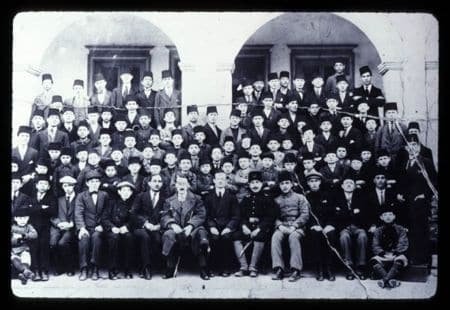

Before the Turkish Republic was established in 1923, the Jewish population of Edirne, for centuries a home to Jews, was 13,000, as reported in the detailed essay “The Jews of Edirne,” by Rifat Bali, an independent scholar specializing in the history of Turkish Jewry. But by 1998, Edirne had three Jews left: Yasef Romano, who was born in 1938, and Rifat and Sara Miftani, a couple who owned a shop there.

Today, the current Jewish population of Edirne is two.

The Jewish presence in Edirne dates back to early Byzantine times, during the rule of Roman Emperor Theodosius I (reigned 379-395 CE). During the Ottoman Empire, Edirne — home to many Jewish intellectuals, scientists, musicians, publishers and merchants — was as central to Jews as Constantinople (Istanbul) and Thessaloniki.

What happened?

The “Turkification” of Turkey: Anti-Semitic Attacks against Jews during the Early Years of the New Republic

In January 1923, provoked by a series of anti-Semitic pieces published in the Pasaeli newspaper in Edirne, residents of Edirne gathered in the city center and shouted, “Your turn to leave this country will come, too! Jews, get out!” After the police were barely able to prevent attacks against Jewish shops, Jews who lived in small towns, such as Babaeski, moved to big cities, such as Istanbul.

Later that year, in December 1923, the Jewish community of several hundred living in Corlu, in Eastern Thrace, was ordered to leave the town within 48 hours. Although the decision was delayed at the request of the Chief Rabbi, a similar order, given to the Jews in Catalca, a town in Istanbul, was applied immediately.

The reason for the anger was clear: Within the Turkification campaign of the new Republic, Armenians and Greeks had been eliminated, but Jews, who were successful merchants, remained.

Prohibitions against Free Movement for Jews

In Anatolia, in June 1923, free movement for Jews was prohibited. Many Jewish merchants who had journeyed to Istanbul from the cities in Thrace — such as Edirne, Kirklareli and Uzunkopru — and Jewish mothers and children who had come to Istanbul because of health or other reasons, were unable to return.

The same prohibition was again imposed in 1925 when the Turkish Ministry of the Interior ordered there to be an area of about 110 km. between the towns of Gebze and Catalca in which Jews could travel. Jews were banned from entering Anatolia without the permission of the Turkish Ministry of the Interior.

“Citizen, Speak Turkish!”

On January 13, 1928, a campaign to force minorities to speak Turkish — with the slogan of “Citizen, Speak Turkish!” — was begun by the Student Union of the Law School of the Ottoman University (today’s Istanbul University); the public use of languages other than Turkish was prohibited.

The whole country was covered with signs repeating this edict. Turkish youths warned minorities to speak Turkish. And the message further spread into the mass media and political circles across the country. Those who did not comply were threatened, beaten or brought to court. Hundreds were reportedly arrested for speaking languages other than Turkish, or had fines imposed.[1]

Committees were established throughout Turkey; posters of “Citizen, Speak Turkish!” were hung in public places and all citizens were urged to speak Turkish. In Edirne, the campaign was conducted by students in an even more severe and anti-Semitic way. Jews were told that those who did not speak Turkish would not be allowed to live a comfortable life or would be driven out of the country. Bakeries were not allowed to bake matzoh for Passover. Some mosques preached that Muslims should boycott Jews and not engage with them.[2]

This campaign, which had started in Istanbul, soon spread to other cities. Edirne’s Jews established a commission that made the following recommendations: “Turkish will be spoken during all meetings. Rabbis will prompt people to speak Turkish in religious ceremonies and rituals. Girl and boy students at Hebrew schools will be obliged to speak Turkish at school as well as outside and in their homes. Signatures of merchants and shopkeepers will be taken [agreeing] that they speak Turkish. In places such as coffeehouses run and used by Jews, waitresses will serve their customers in Turkish.” Coffeehouse owners hung signboards that read, “Speak Turkish;” Rabbis told Jews to cooperate.

The 1934 Turkish Resettlement Law

The 1934 Turkish Resettlement Law, based on being Turkish and having Turkish as a mother tongue, resulted not only in the forced assimilation of all non-Turks, but also in their forced displacement.

Jews who had lived in Eastern Thrace were forcibly sent to Istanbul; and scores of Kurds in Kurdish town and cities were forcibly moved to western cities across Turkey.

Fuente: churchandstate.org.uk

eSefarad Noticias del Mundo Sefaradi

eSefarad Noticias del Mundo Sefaradi

Texto bastante elucidativo. Provavelmente ajude a entender a razão da minha família paterna, que morava há séculos na cidade de Lule-Burgáz, na Trácia, tenha decidido migrar para o sul do Brasil em 1926. Nelson Menda