Edouard Brandon’s rare 19th-century depiction of a Jewish man reading is even more absorbing today

By Sebastian Smee

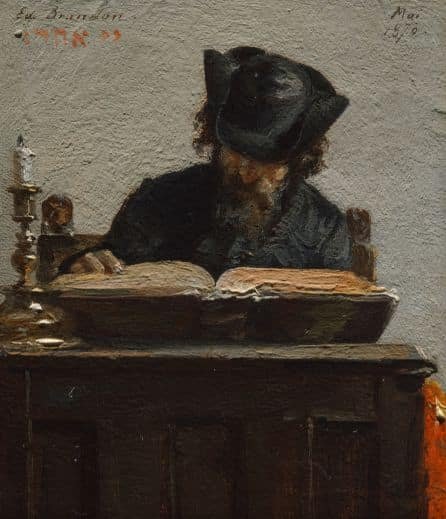

BOSTON — Ever since curators at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts pulled this painting of a Jewish man out of storage just over a year ago, I have returned to it repeatedly. It’s a tiny thing — just over five inches high and just under three inches wide. Both the man’s subtly unsettled body language and the brushwork make it feel modern — which it is: It was painted in 1870. But “Juif Lisant” also conveys the hallowed interiority and penumbral light of 17th century Dutch genre painting (one thinks of Rembrandt or Gerard ter Borch).

The image is dwarfed by its frame, which is wider on each side than the painting itself. It casts a shadow over the top of the picture, obscuring the part where the artist, the Frenchman Edouard Brandon, has inscribed, beneath his name, “The Lord is One” in Hebrew. The words are taken from the Shema, the Jewish prayer recited morning and night.

The image is dwarfed by its frame, which is wider on each side than the painting itself. It casts a shadow over the top of the picture, obscuring the part where the artist, the Frenchman Edouard Brandon, has inscribed, beneath his name, “The Lord is One” in Hebrew. The words are taken from the Shema, the Jewish prayer recited morning and night.

As news of rising anti-Semitism breaks daily, my curiosity about the artist and his devout subject deepens. Who was Brandon?

That almost no one knows is strange, because he participated in one of the most momentous exhibitions in the history of art: the first Impressionist exhibition, held in 1874. The son of a Parisian art dealer, Brandon had trained at the Ecole des Beaux Arts before studying under Camille Corot.

Like Camille Pissarro — the only person to participate in all eight Impressionist exhibitions — Brandon was a Sephardic Jew. He was from a wealthy family. His family’s synagogue in Bayonne, on the French side of the Pyrenees, served their local community throughout the 18th century.

Brandon himself had a gift for friendship. In Italy in the late 1850s, he met and befriended both Gustave Moreau and Edgar Degas. He remained close to Moreau and over the years he and Degas exchanged works. At one point Brandon even owned Degas’s very first painting of a dance class.

Degas had many Jewish friends. But during the Drefyus Affair — the divisive political scandal involving a military officer of Jewish descent who was accused of treason — he became virulently anti-Semitic. His willingness, late in life, to cut off even close Jewish friends suggests how cruelly abstract anti-Semitism can be and, at the same time, how frighteningly close to the psyche’s surface it lurks. Also — chasteningly — how little it takes for intelligent people to feel licensed to say and think the stupidest, most shameful things.

When Brandon returned from Italy, in 1863, he focused increasingly on Jewish themes, especially synagogues and Torah lessons. One small painting, called “The Master and the Student,” appears to be a pendant to “Juif Lisant”: It shows the same bearded man in the same cocked hat standing at the same lectern. Instead of reading, he is rebuking a child, who duly hangs his head in disgrace. On the blackboard behind him is a drawing of a pig.

“Juif Lisant” is the better painting. Dispensing with cute anecdote and coy suggestion, it shows a man absorbed in a book — a big, important book. The candle has burned down. One hand prepares to turn the page. For now, however, history is suspended and the world around him holds its breath.

Fuente: washingtonpost.com

eSefarad Noticias del Mundo Sefaradi

eSefarad Noticias del Mundo Sefaradi