New-York Historical Society exhibit looks at Jews before the Revolution and after

You know that feeling that there are Jews just about everywhere? Not many in any one place, necessarily, but at least a few of them just about always. Well, it’s true.

Among those places was the Caribbean, in the seventeenth century, as well as in North America just a bit later, as “The First Jewish Americans: Freedom and Culture in the New World,” an exhibit at the New-York Historical Society in Manhattan, shows. That is, of course, well before the birth of the American Republic.

Of course, Jews were there — in the Caribbean, in Mexico, in New York and Philadelphia and Charleston and Newport — because Jews always were running; these communities were established by European exiles, driven out of their homes by bigotry in general, and by the Spanish Inquisition in horrifying particular.

It’s not surprising, as one of the exhibit’s curators, Debra Schmidt Bach, points out, that the names of the congregations those immigrant Jews established had emotional, forward-thinking names — the Hope, the Remnant, or the Salvation of Israel, to name just a few. (That’s Mickve Israel in Savannah, established in 1735; Shearith Israel — The Spanish Portuguese Synagogue in Manhattan, established in 1654, and Jeshuat Israel, better known as the Touro Synagogue, in Newport, R.I., established in the 1670s.)

Jews also seem always to be involved in social issues, and sometimes they’re on the wrong side. That was true about slavery; as the exhibit shows, the Jewish community was not entirely free from the taint of this country’s original sin. They were genuine Americans, then as now.

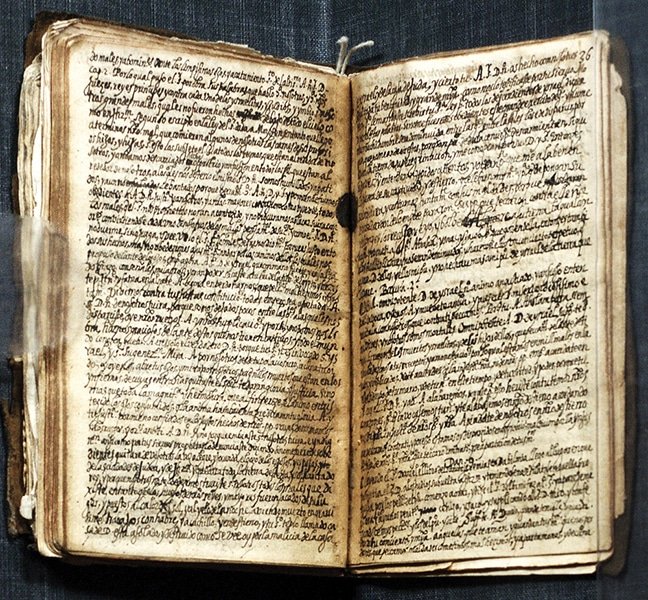

The exhibit opens with a visually not particularly compelling but historically heart-stopping document, the memoir by Luis de Carvajal the Younger. De Carvajal was a converso, a Jew who had to become Catholic, a Spaniard who became a Mexican, all to escape the reach of the Inquisition. De Carvajal the Elder, his uncle, was a governor of territory in Mexico; the younger, after torture, named names to the Inquisition but was burned at the stake anyway. He was 30 when he was brutally murdered, in 1596.

The memoir had vanished, mysteriously, from the Mexican government’s archives, and reappeared, again mysteriously, for sale, many years later. It was bought by the American Jewish collector Leonard Milberg, who returned it to the Mexican government. Mexico loaned the New-York Historical Society this object, but much of the display comes from the collections of Mr. Milberg and his family.

Meanwhile, there this book is, a physical remnant of a terrible time. Somehow it has survived.

And artifacts from the Caribbean show how well Jews were integrated into society there. A map of Suriname from 1718 shows local landmarks, including synagogues. There is an 18th-century document that includes a religious service for circumcising slaves, although, Dr. Bach said, no one is exactly sure what that meant for the slaves who were so marked. Did they become Jews? Or did they remain the property of Jews? And speaking of circumcision, there also is a list of mohalim in Europe and the Caribbean.

The exhibit also includes two paintings by Camille Pissarro, who was born to Jewish parents on St. Thomas in 1830.

Next, the exhibit moves to the heart of the New World, the settlements that perched at the Atlantic shore. Jews came to New York early; its governor, Peter Stuyvesant, notoriously did not want them, and kept them waiting as he importuned his employers, the Dutch West India Company, to reject them. But the company cared far more for business, and for the Jews’ well-know ability to conduct it well, then for their peg-legged governor’s intolerance, so they were allowed to stay.

Those Jews established Shearith Israel way downtown in Manhattan, where everyone lived, very early; it still thrives today, uptown, on Central Park West, and it has spun off Ashkenazi communities that also continue to flourish.

The exhibit includes many artifacts from Shearith Israel, including silver-and-brass rimmonim — a pair of belled crowns that go on top of the wooden poles that hold a Torah scroll. They’re beautiful, intricately made objects, created by silversmith Myer Myers, who belonged to Shearith Israel. It also includes a Torah scroll defaced and burned by British soldiers during the Revolutionary War.

There also are six paintings of members and branches of the community’s most prominent families, the Franks. Painted by Gerardus Duyckinck and dating from the 1690s into the middle of the 18th century, the paintings show the family as aristocrats; Jacob Franks, the paterfamilias, one of the founders of Shearith Israel, looks full-on Whig. (Yes, he’s wearing one. A very full one.)

The exhibit includes a prayer book from 1776 — “Prayers for Shabbath, Rosh-Hashanah, and Kippur, according to the Order of the Spanish and Portuguese Jews” — and an English and Hebrew grammar book from 1771.

And there also is the upsetting, straightforward account book documenting Martin Lopez’s purchase of property — five slaves. Elsewhere, another New York Jew, Jacob Levy Jr., is said to have freed four of his.

The Jewish community, like the rest of New York, was divided in its loyalties as the revolutionary war grew unavoidably closer. Some supported the new Americans — Haym Salomon, a Polish-born Sephardic Jew who moved to New York, provided the revolution with vitally important funding. But others stayed loyal to Britain. The New-York Historical Society displays a faded document, signed by Abraham Gomez, Moses Gomez Jr., Uriah Hendricks, and other Jews, as well as non-Jews, pledging their loyalty to British Admiral Richard Howe and his brother, General William Howe.

Philadelphia also attracted many Jews; some went there before the revolution but others fled there during or even after. It provided them with a haven from the more British-leaning New York community. The exhibit includes the Resolution of Non-Importation made by Citizens of Philadelphia in 1776, signed by some of the city’s Jews. It also includes paintings of the Gratz family; the merchant Barnard Gratz signed the resolution and provided supplies to American fighters. There is also a lovely portrait of his niece, Rebecca Gratz. In real life, she set up the Female Hebrew Benevolent Society; in fiction, she was Sir Walter Scott’s model for Rebecca, Ivanhoe’s true love, the Jewish girl he does not marry. (Rowena was the sappy heroine who gets him in the end.) Like Scott’s Rebecca, Rebecca Gratz never married.

Charleston had more Jews than any other American city in the 19th century. The Reform movement in the United States began there, when the leaders of Congregation K.K. Beth Elohim refused a request to include English in services. The disgruntled congregants left and established their own organization, the Reformed Society of Israelites for Promoting True Principles of Judaism According to Its Purity and Spirit. The exhibit includes a painting of the elegant Orthodox shul, along with a copy of the Reformed Society’s prayer book.

The exhibit does not look at the Civil War; that’s one period of American Jewish history that’s been well covered elsewhere, Dr. Bach said. But it does include information about other American Jews, including figures as diverse as the War of 1812 hero Commodore Uriah Phillips Levy and the New Orleans-born composer and pianist Louis Moreau Gottschalk, whose father was Jewish. There is also some information about Lorenzo Da Ponte, who was born in Italy but moved to New York, where he spent the rest of his life. Who knew that Mozart’s librettist was Jewish? But actually he wasn’t, so it’s okay not to have known. Da Ponte was born a Jew but converted to Roman Catholicism and ended his days as a priest.

The exhibit goes on to discuss Jews as artists, scientists, doctors, lawyers; finding themselves in a society that on the whole accepted them, and certainly accepted them more openly and thoroughly than any other place at any other time, they breathed deeply, thought freely, acted authentically, evolved naturally, and flourished.

The exhibit ends with a quick look at the places that were home to large numbers of Jews by the end of the 19th century — Cincinnati, San Francisco, Los Angeles. Jews, in other words, moved west along with everyone else. And that’s pretty much the message of this exhibit. In the United States, Jews were able to retain their Jewishness, allow it to change in response to changed conditions, and still be part of the larger world.

That’s always been part of the promise of America. Let us hope it always will be.

What: The New-York Historical Society presents “The First Jewish Americans: Freedom and Culture in the New World.”

Where: 170 Central Park West, at the corner of 77th Street, in Manhattan

When: Now through February 26

What else: On Monday, January 23, at 3 p.m., co-curator Debra Schmidt Bach will lead a gallery tour.

On Monday, January 30, at 6:30 p.m., the New-York Historical Society’s president and CEO, Louise Mirrer, will moderate a discussion between Dale Rosengarten, founding curator of the Jewish Heritage Collection and director of the Center for Southern Jewish Culture at the College of Charleston, and Rabbi Meir Y. Soloveichik of Congregation Shearith Israel — the Spanish Portuguese Synagogue.

On Wednesday, February 15, at 6:30 p.m., the emeritus director of the ADL, Abraham Foxman, and writer Thane Rosenbaum will discuss Jewish-American history.

For more information: Go to www.nyhistory.org or call (212) 873-3400.

December 1, 2016

Source; Jewish Standrad

eSefarad Noticias del Mundo Sefaradi

eSefarad Noticias del Mundo Sefaradi